Being patient with choice

Choice is such an elemental part of marketing that it’s one we rarely explore in its own right. It would be like discussing air. Choice is a given, a state that has to exist before marketing makes any sense at all, the invisible milieu that envelops all our endeavours and striving.

Marketers deploy their research budgets to understand more about their own brands and those of competitors, or about customers and the category, but not to gain insights into the abstract notion of choice itself, and what consumers feel about it. Academics have taken a look, though, and what they’ve discovered is that choice is a double-edged sword.

While it might be flattering to have 87,000 Starbucks options for your morning coffee, a study by US psychologists Hazel Markus and Barry Schwartz concludes that “too much choice can produce a paralysing uncertainty, depression and selfishness.”

If choosing is not unalloyed joy for consumers, that’s hardly your problem as a marketer. Option overload is how our capitalist way of life works, for good or bad; your task is to gain advantage in the prevailing milieu.

Perversely, choice tends to be brought out into the open, and championed as a public good, by the institutions that have long suppressed it. The NHS was a centralist, option-free monolith for 52 years until Tony Blair and Alan Milburn banged the drum for reform in 2000 and promulgated the rights of patients to select their care providers.

Now Prime Minister David Cameron has taken up the baton, insisting, despite recent reversals, that the coalition is right to propose “more choice and control for patients.” He should think twice before getting too breathless about the allure of patient choice, however, since patients are apt to see it as a burden, not a benefit.

Nor should the link between choice and improvement in standards be made too slickly. Choice itself is but one of three market forces that, eventually, lead to product and service improvement. The others are meaningful difference, without which choice becomes irrelevant, and increased reward for the chosen, without which there is no incentive to improve.

In free, commercial markets, these three forces work seamlessly and swiftly to bring about steadily rising standards as brands vie, improve, gain or play catch-up. In controlled markets such as health, meaningful difference and increased reward have to be arranged far more clumsily, so the process is slower and more diffuse.

What this means, for a patient making a choice between providers today, is that the long-term improvements that ensue from their decision, and those of thousands of patients like them, will materialise only years down the line. There will be a benefit eventually – but mostly for others, much later, not for them, today.

So in matters of health, exercising choice amounts to an act of selfless citizenship, one to be made at a time when people are feeling, justifiably, at their most selfish. This isn’t about a latte versus a cappuccino, but, at the extreme, a matter of life and death. No wonder patients experience that ‘paralysing uncertainty’, and just want someone more qualified to decide for them.

Choice might be a natural element of marketing, but for the NHS reforms to stand a chance, someone smart has to get out there and start marketing the true benefits of choice. It won’t be easy.

The NHS Constitution, established in 2009 during Alan Johnson’s time as secretary of state for health, defined legal rights for patients, the public and staff. These covered seven areas, one of them being informed choice.

Within the scope of informed choice, citizens have the right to choose their GP practice; to express a preference for a particular doctor within their GP practice; to make choices about their NHS healthcare; and to have the information to support these choices.

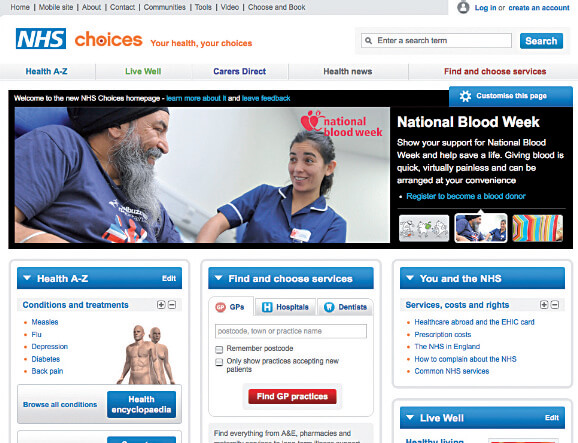

NHS Choices a resource for patients

The NHS Choices website, launched in 2007, provides patients with a wide range of information about health and health services. The site is a reliable source for information on conditions and treatment, and helps patients decide in which hospital they want to be treated.

Analysis of data from choice pilot projects showed that patients are less likely to choose treatment with an alternative provider if they are older, particularly those aged 60-plus; have lower education levels; have family commitments; or have an annual income of less than £10,000.

In his speech to NHS staff in London two weeks ago, David Cameron claimed that a study published by the London School of Economics found that hospitals in areas with more choice “had lower death rates.”