Biting the bullet

As a young account manager in advertising, one of my duties was to ensure that the slides for big meetings were all present, correct and the right way up in the carousel.

Yes, carousel. In those Palaeolithic days, circa 1989, slide content had to be shipped out for processing 48 hours in advance, then ordered on a light-box and stacked oh-so-carefully in the round plastic container – 80 in each, I recall. Sometimes we would head into a meeting with a small tower of these carousels and the looks on the recipients’ faces told us they knew what they were in for.

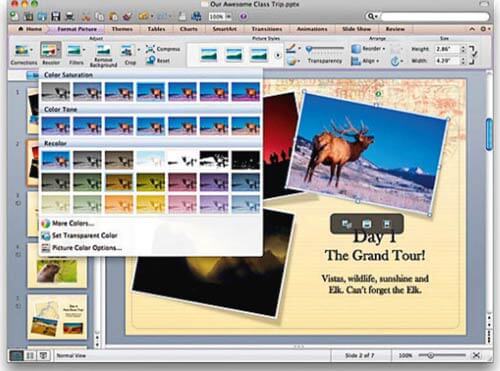

When PowerPoint came along, life got easier for young account managers, who could now devote more time to sitting at the back of focus groups, cutting up images for mood boards, and drinking.

Two decades on, it has become fashionable to blame PowerPoint for the torture of the bullet-point format and dreary slide content, but these sins, I can tell you from experience, long preceded the technological advance.

What PowerPoint has done, though, is make the offences easier to commit. Like a mini-fridge in a bedroom, the sheer ease of the programme encourages excess where moderation would be wiser. Another chart? Why not? It is the matter of a moment.

There is also something about those default settings that nudges you, not just toward bullet-point ordering, but also to hierarchical nesting, with smaller dots and dashes everywhere, like a mangle of Morse code.

If you’re one of those marketers who, like me, feels guilty about too much charting, and makes an annual resolution to do less, there is now a body of academic research to stiffen that resolve.

A healthy corrective is Yiannis Gabriel’s 2008 analysis of studies into how the medium corrupts the message. An important finding is that bulletpoint lists impart an unjustified authority, and that people infer a causal connection between one point and the next, even when there is none.

Gabriel actually experimented in his lectures, first rearranging bullet points randomly across charts. He was surprised to find it easy to extemporise in his presentation of the resulting nonsensical order, and more surprised that his students appeared not to notice.

The data-visualisation guru, Edward R Tufte, has long inveighed against PowerPoint, accusing it of degrading the quality of information. In a biting 2003 essay, he even implicated the system in the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster.

Tufte’s counsel is to hand out printed notes before presentations. He is also right to lampoon the common practice of simply copying the PowerPoint charts into the take-away document, which, he says, are frequently ‘physically thick and intellectually thin’.

Most serious for marketers, though, is that, in a discursive discipline, any form of chart presentation sets up an uncomfortable, one-way dynamic.

Here are the links, if you want to take a look at the Gabriel and Tufte papers (both behind a paywall). Meanwhile, it’s a case of practising what they preach, and reverting to a more open, chart-free style whenever possible. It won’t be easy to forgo the convenience of PowerPoint, but it is time to bite the bullet.

PowerPoint a slideshow to forget?

PowerPoint began its life as an Apple Macintosh programme called Presenter, the brainchild of two Berkeley tech geeks back in 1983. Only in 1987, when Microsoft bought its owner Forethought for $14m and adapted the software to its Windows OS, did PowerPoint as we know it today come into being.

Nowadays, according to Microsoft’s own estimate, about 1m PowerPoint presentations are going on at any one time. That doesn’t mean that much information is sinking in, however: a study by Rexi Media found that people forget about 70% of slides within two days of the presentation.

The average slide contains 40 words, usually laid out in a bulletpoint format.

Although Guinness World Records does not recognise the world’s longest PowerPoint presentation as an official category, consensus on the web points toward Rebekah Rousi’s 2008 talk at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels. Breaking down the structure of language took her 27 hours and more than 800 charts.

A final word from Edward Tufte: ‘Power corrupts. PowerPoint corrupts absolutely.’