Courage and consensus

Two of the hardest words to say in marketing are “I disagree”. It might not seem like that, of course, if you imbibe your marketing discourse from the ever-bubbling spring of Twitter or books on the business shelves at airports.

In those formats professionals do not merely beg to differ but insist on bulldozing the intellectual ground that others stand on. Twitter exchanges will kick off with insults like ‘More nonsense on brand purpose from @someone’, while book titles promise to inform the hapless practitioner ‘Why everything you thought you knew about [sub-topic goes here] is wrong’.

But this is disagreement at a distance, license through a lens. The blogger, tweeter, author – or columnist, for that matter – who strides out on a contentious path is doing merely what is necessary to make a dent in the rankings and fulfil minimum expectations of the reader. To declare that you will be a ‘fearlessly uncompromising voice’ in those vectors is to settle into a well-established groove of iconoclast convention.

It’s another matter altogether when it is just you, a mid-rank marketer, around a big table of peers and colleagues in a consensus-driven culture, with everyone closing in on an agreed way forward for targeting, or distribution or brand strategy, and a voice in your head going “this isn’t right”, accompanied by a disconcerting awareness that your pulse is racing.

To say, simply and clearly, in that context, “Look, I disagree with this approach and here’s why”, takes a lot more courage than firing off a contrarian tweet.

But I do mean ‘simply and clearly’. I’m not talking about donning the camouflage of ‘playing devil’s advocate’ or ‘suggesting a challenge’. These tempting devices depersonalise the protest and lead others around the table see the contrasting positions as routines to be played out. A sequence of almost choreographed ifs and buts can then be gone through, and at the end the majority view will be carried as normal – accompanied by a satisfied sense that ‘all opinions have been explored’.

Open-sight dissent, conversely, in any human group, is curiously distressing – even when you are virtually certain you are right.

In a classic psychology experiment a volunteer would be shown into a room with a row of eight chairs and asked to sit at one end. Others would gradually file in and occupy the other chairs, and the experimenter would ask the group to perform a simple, repeated task.

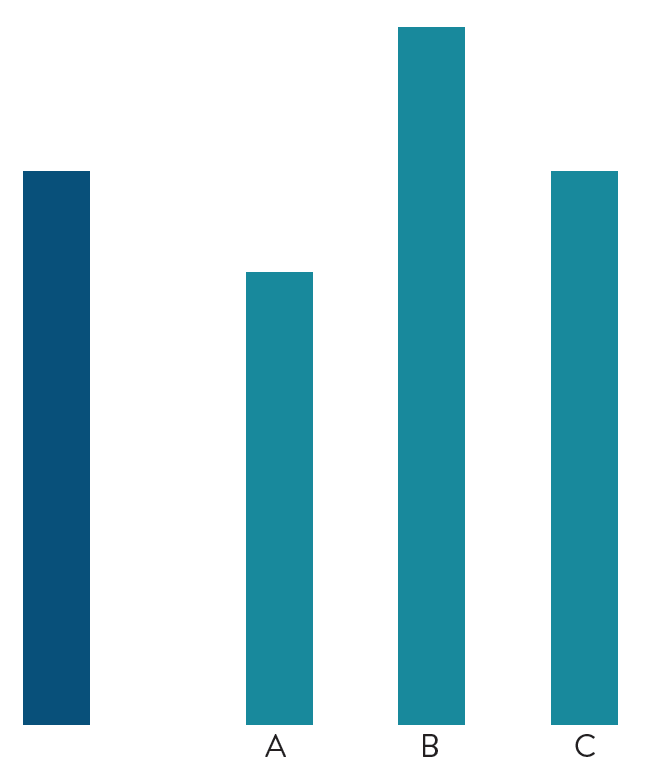

Each participant viewed a card with a single straight line drawn on, alongside another with three lines of varying length – only one of which corresponded with the length of the line on the first card. Starting at the far end of the row, the group had to call out one by one which it was: A, B or C.

To our volunteer, the task seemed stupidly easy. It was obvious which line was the same length – corroborated when all the others ahead called it out. But then something disturbing would happen. For subsequent rounds – when the choice was equally obvious – the others ahead would call out a different line. So when it seemed clear that the answer was C, they would all agree on A.

And so it went on. About three-quarters of the time, those calling ahead would agree on a different choice. And our volunteer – though all but sure each time they were right – would fall in with what the others said. Those others, of course, were stooges. Our volunteer was the patsy. Few stood their ground. Almost universally they would settle into a pattern of concurrence. Open, solus disagreement, even in this low-stakes environment, would be deeply unsettling.

But around that big corporate table, it isn’t low stakes. And the others aren’t stooges. At the extreme, your reputation, and perhaps even your mortgage, might be on the line. So I am not going to say you should automatically stick your neck out for the good of the organisation.

Or maybe I am. Because when you think about it, what are the alternatives? Sit on your hands and go along with the mood in the room, only to witness somebody else, later down the meeting, come out with the very same objection you had suppressed, to the grudgingly admiring glances of the team?

Or worse: come out of the meeting never having said your piece, and become a fully paid-up member of the crew that sails the agreed strategy forward, only to see it strike the very iceberg you had wanted to warn about – crying “I knew this would happen”, as the fatally holed vessel goes down?

THE ASCH CONFORMITY EXPERIMENT

Participants were asked to choose which line on the right matched the one on the left. Stooges would give the wrong answer and volunteers would follow the crowd

There will be times in any marketer’s career when their combination of experience and specialism will help them see consequences of action with greater clarity than their peers – even when those peers are agreed; times when they should find the courage to show the others why they have picked the wrong line. Both the brand and the business need it.

And so does the wider industry. Compared with other corporate functions such as finance and operations, marketing is a diffuse discipline with fewer proximate metrics to act as guardrails and more scope for interpretation. That makes it exciting, but also unwieldy when teams get large: too many opinions around the network and that global strategy is going nowhere.

To solve the problem, there has been an ever-intensifying emphasis on consensus marketing, with processes and incentives designed to promote it. But – as solutions are apt to – this one merely sets up the next problem: group-think, ossification, blindness to unintended consequences.

It’s not that our discipline needs more self-styled mavericks who make a career of espousing contrarian views seemingly for the thrill of it. They will tend to be wearily tolerated and studiously ignored. But it does need those who, when it matters, can stand up and be counted on to deliver their thoughtful, fact-based, minority-of-one counter-argument – no matter how disagreeable the accompanying emotions might be.

These are some of the decisions that provoke the greatest potential for disagreement in modern marketing – with minority voices often having a tough time getting heard above the clamour for the fashionable option.

Wide or narrow targeting

This has always divided marketing teams, with those who want to give the brand the biggest possible canvas challenged by those for whom segmentation was the more sophisticated approach. For a long while, segmentation held sway – until Professor Byron Sharp showed the huge significance, for brands in most categories, of the long tail of light buyers.

Parity or difference

For most marketers – and all agency people – this is a no-brainer: marketing is all about differentiation. But Professor Kevin Keller has shown that things are not that simple. He observed that most new launches flop not because the brand has failed to communicate its difference, but because it has omitted to set out its ‘points of parity’ – the must-haves, features and associations that serve as a reference for the category.

Digital or traditional media

Or both, of course. High priest for the ‘digital, digital, digital’ mantra is Gary Vaynerchuk, who has recommended that marketers spend every dollar of the budget on just Facebook and Instagram. But traditional media still has its adherents: in last year’s IPA Effectiveness Awards, a return to mass-market TV was behind the winning entries for the AA, the British Army, Yorkshire Tea, Weetabix and Covonia.

Noble purpose or not

Purpose has become fashionable in recent years, encouraged by Jim Stengel’s book, Grow, which sought to show that purpose-driven companies were more successful. But this has been countered by critics such as Richard Shotton, who have shown no causal link exists between purpose and profit. Both miss the point: higher-order purpose is about standing above commercial considerations, or it is nothing but a cynical ploy. At the extreme, its adherence might imply financial sacrifice. Is it still a good thing? Discuss.