Failing to learn

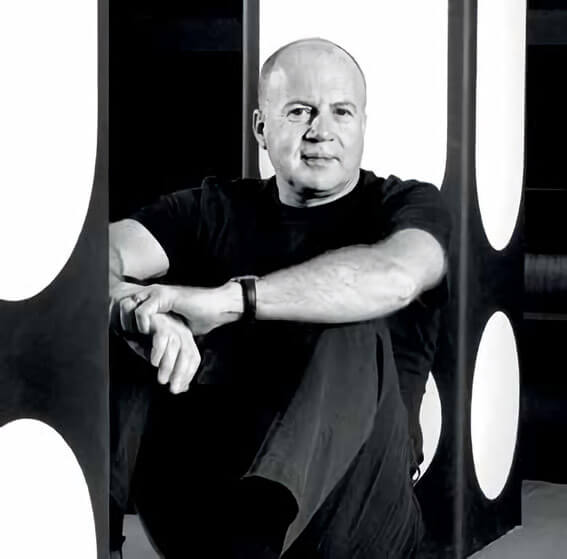

What struck me most about the recent Kevin Roberts episode was the oddness of the homily he chose to sum up the mess he had got himself into: “Fail fast, fix fast, learn fast.” For Roberts – who combined his role as Saatchi & Saatchi executive chairman with that of head coach for the entire Publicis Groupe – this has apparently been an “enduring maxim”.

I can think of better ones. I can think of ones that might inspire more confidence in the agency he has managed for 20 years. This one belongs right up there with “we suffer fools gladly”. What kind of message does it send out to marketers who are thinking of entrusting their brands to the teams that this coach trained? “Hey, we can help you fail in a heartbeat, and we’ll be right there speed-learning with you afterwards.”

I think marketers – with their targets, anxieties and hard-won budgets – would prefer that learning to have been done long beforehand, deeply, completely and professionally. While marketing endeavour always carries risk, and while failure is always a lurking possibility, any sane marketer would want the agency to use its expertise to steer away from it, deploying all the intelligence, knowledge and foresight it can muster. Why welcome failure with open arms?

My guess is that Roberts feels the same way about his own important advisors – like the lawyers he is doubtless huddled up with now to ensure the best severance terms from his $4m contract. Does he want to work with guys who think it’s fine to make a few wrong calls and try to learn on the hoof? Or would he prefer to side with a team that has done its homework and knows how to parry and better everything thrown at it from the opposing side?

Failure is overrated – something that’s become fashionable to embrace in a clever, “dirt is good” kind of way. Like a lot of glib nonsense that has found its way into the marketing world, “fail fast” and its variants – “fail smart”, “fail forward” – have come to us via Silicon Valley.

In a lean, digital start-up, where it’s a relatively simple matter to develop variants and test them in an A/B split, a rapid, probe-and-learn approach makes sense. When you hit a wall, try something else and adapt quickly. There is little to lose and the variables can be sufficiently isolated to make for confident conclusions.

It is wildly naïve to extrapolate the formula to the management of established brands in complex, mature markets, where the relationship between cause and effect is diffuse and variables are everywhere. Even when failure does strike with clear and certain force, the one thing you can’t do is learn fast.

It is wildly naïve to extrapolate the formula to the management of established brands in complex, mature markets, where the relationship between cause and effect is diffuse and variables are everywhere. Even when failure does strike with clear and certain force, the one thing you can’t do is learn fast.

Recently, in a project briefing, a marketer explained to me that they had tried to reinvigorate a fading brand leader by switching from a highly rational to a purely emotional communications approach. “It didn’t work,” she continued, “so we need to go back to a rational story again.”

Common sense or overcorrection? That particular emotional approach didn’t work but perhaps a better one would. Perhaps a stronger consumer insight would have made all the difference. Could a hybrid message have cut through, with a bit of tweaking to the segmentation? Or might a deeper analysis of the data suggest that innovation is the only solution and, without it, no communications strategy will achieve much? This is marketing forensics and it takes time. Those coached to look for the quick fix will be guaranteed disappointment.

There is a lot of talk in our industry about giving people permission to fail. But do you know what? They are perfectly capable of failing whether given permission or not and it will feel wretched when they do, no matter how supportive the corporate culture may be. It would be better to give people permission to do the things that make failure less likely – which is something they rarely get right now.

Give them permission to learn slow – to enhance their marketing skills with continuous training or to embark on an MBA so that their judgment can be more commercially grounded and astute.

Give them permission to be less rushed when it comes to understanding consumers too – swapping hasty focus groups for the academic ideal of “triangulation”, where different research methodologies are interleaved to reveal and corroborate underlying themes.

“Learn slow, fail less” would be the variation I suggest to the Roberts maxim. It is, dare I say, a bit less macho than the original, a lot less shoot-from-the-hip. But that is not to imply a stultifying excess of caution. Imagination and daring will always be vital to success in marketing – but they are potent forces best deployed by those who have taken the time to master best practice and have done everything they can to understand the nuances of their particular market, consumer and brand.

Failure isn’t fun. Like death, it happens to us all, but we’d all really rather it didn’t. Surely even Roberts, as he contemplates a sadly ignominious end to a successful 47-year career, agrees deep down with that.

“Success is most often achieved by those who don’t know that failure is inevitable.”

– Coco Chanel

“So go ahead, fall down. The world looks different from the ground.”

– Oprah Winfrey

“Some failure in life is inevitable. It is impossible to live without failing at something, unless you live so cautiously that you might as well not have lived at all – in which case, you fail by default.”

– JK Rowling

“Women, like men, should try to do the impossible. And when they fail, their failure should be a challenge to others.”

– Amelia Earhart

“Failure is an important part of your growth and developing resilience. Don’t be afraid to fail.”

– Michelle Obama