Great brands give you hope

I always open my MBA marketing classes and routine brand workshops the same way, by asking the people in front of me to give me examples of what they would deem ‘great brands’. And the same ones come up every time: Apple, Nike, Red Bull.

The process from there is one of deconstruction, to turn to the question of what these brands have done to become so amazing, and what secrets and lessons marketers might draw from them.

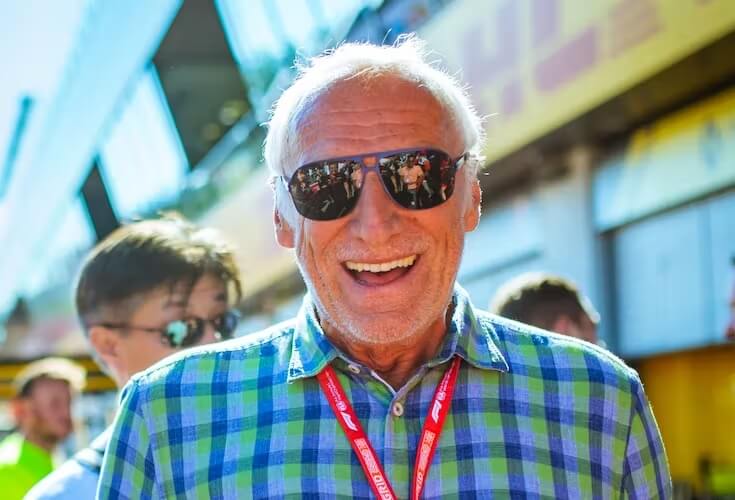

So let’s do that exercise here, but for just for one of them – for Red Bull, in honour of its cofounder and mentor-in-chief, Dietrich Mateschitz, who died earlier this month.

How did Red Bull grow from zero, with a weird-tasting canned drink as its sole and unlikely tilt at posterity, to establish an entire category and achieve a brand valuation somewhere in excess of €15 billion? What are the marketing themes we can greedily extrapolate?

There are many, and each one could make a case study to support a different marketing dogma, for those who tend to attach themselves to such things. For every branding doctrine out there, you could find advocates who would embrace Mateschitz as one of their own.

There are countless marketers and agency staffers, for example, who are drawn to the idea of challenger branding – the brainchild of Adam Morgan, who established the concept with his 1999 book Eating the Big Fish. Could that be Red Bull’s big secret? That it started and continued as a streetfighter challenger brand?

One of the challenger project’s tenets is that you don’t win by outspending the competition but outthinking them. Mateschitz blindsided Red Bull’s natural competitors with an asymmetric push into a then unsung niche – energy drinks – and by adopting guerrilla communications tactics. While the likes of Coke and Pepsi were spending big bucks on traditional advertising, he was out on the streets depositing empty Red Bull cans among the garbage outside selected clubs, so passers-by could see what the cool crowd were drinking – even if, as yet, they weren’t.

A challenge to the ‘challenger’ theory might emanate from the evidence-based marketing school, with its locus at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute at the University of South Australia.

Its own tenets have been set down in uncompromising prose by Professor Byron Sharp, in his 2010 book How Brands Grow. Salient among them is that brands need to achieve ‘mental availability’, through the application of distinctive and consistent brand assets.

Red Bull would appear a textbook example. Its charging-bulls logo, red-on-blue colour coding and ‘gives you wings’ slogan are unchanged since launch in 1987. The brand has occasionally played with them for special promotions or events – ‘consistent but fresh’ was how Mateschitz summed up the approach – but three decades on, they remain essentially intact.

Fame is another quality the evidence-based school promulgates, and when Red Bull launched a skydiver for the highest-ever altitude jump, live-viewed by a record 9.5 million people, you could say it put a tick in that box, too.

Sharp and other evidence-based hardliners have been known to lampoon the notion of consumer emotional engagement as important in branding, since they deem its underlying point – loyalty – a marketing delusion

That won’t stop advocates of emotional-engagement branding pointing to Red Bull as evidence that their own doctrine is the one to follow. Mateschitz never targeted wide, but sought to foster a strong sense of in-group identity, refusing to sell stock to certain outlets when it launched in new markets. ‘We don’t bring the product to the people,’ he declared, ‘we bring people to the product. Red Bull isn’t a drink, it’s a way of life’.

Who else is out there with a pet marketing theory that might attach itself neatly to the Red Bull success story? The ‘digital first’ crowd might want to make its case and has plenty to grab hold of. Here was a brand that didn’t just dabble in social media and separate out a few of its team into ‘digital marketing’, it created an entire, multi-platform content media company. With Red Bull, digital didn’t just support the product, it became a product, and a profitable one, too.

Finally, winging in from California, we have the ‘fail fast’ marketing mantra, the silicon-valley insistence that experimentation and rapid learning are the secret to breakthrough innovation and growth. Mateschitz was certainly prepared to fail and not be fazed. Many of the brand’s initiatives didn’t make it – LunAqua water, Red Bull Cola, energy shots – and the original product itself had looked to be doomed at the outset. ‘Disgusting’, was the view of trialists in research. But some liked it, Mateschitz understood the power of polarity, snowboarders and ravers started to grab it and the rest was blood, sweat, toil and success.

The presence of a great brand in a routine marketer’s line of sight can be envy-inducing. ‘How come those guys are having all the breaks?’ But great brands give us all hope, precisely because their success is always multifactorial. If it were down to one single thing – a proprietary ingredient, say – there would be nothing we could emulate. But look closely at a great brand case and you will find many points of entry to extrapolate to your own category, product and brand, no matter how different they might seem at first.

Nonetheless, if we come up a level of abstraction, it is possible to crystallise the message of Mateschitz – and the late Steve Jobs, and Nike’s Phil Knight – in a single principle. It is this:

Anyone can create a great brand. All you have to do is everything.