Life Brands

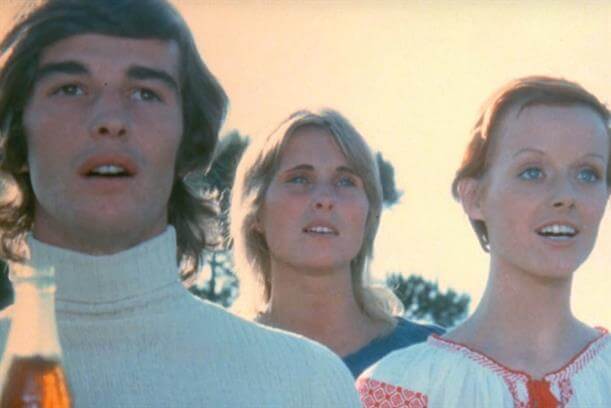

The demographic group that sealed the election for the Conservative Party, providing 38% of its entire vote, were skinny, long-haired idealists in flares, who vowed never to trust anyone over 30 and liked to chant at Glastonbury that “if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem”.

At least, they were once, many decades ago, long before they got richer and fatter and more conservative in every sense. Long before their obsessions veered to property prices and triple locks. Long before they turned 65.

It must be all but impossible for the actual 18-24 group now – the ones who turned out in force for Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour – to picture that pensioner cohort as the arty teens and rebellious students they once were. It’s probably hard for the older group to imagine it themselves, to remember and identify with the “youthquake” they were once part of.

And it will be harder still – not that they’ll try – for the youthful Corbynistas of 2017 to imagine that they, too, will change out of all recognition over the coming years. Change styles, change tastes, change priorities, change allegiances.

Change brands too. But not all brands. Some will come along for the ride. Which is an amazing feat, when you think about it.

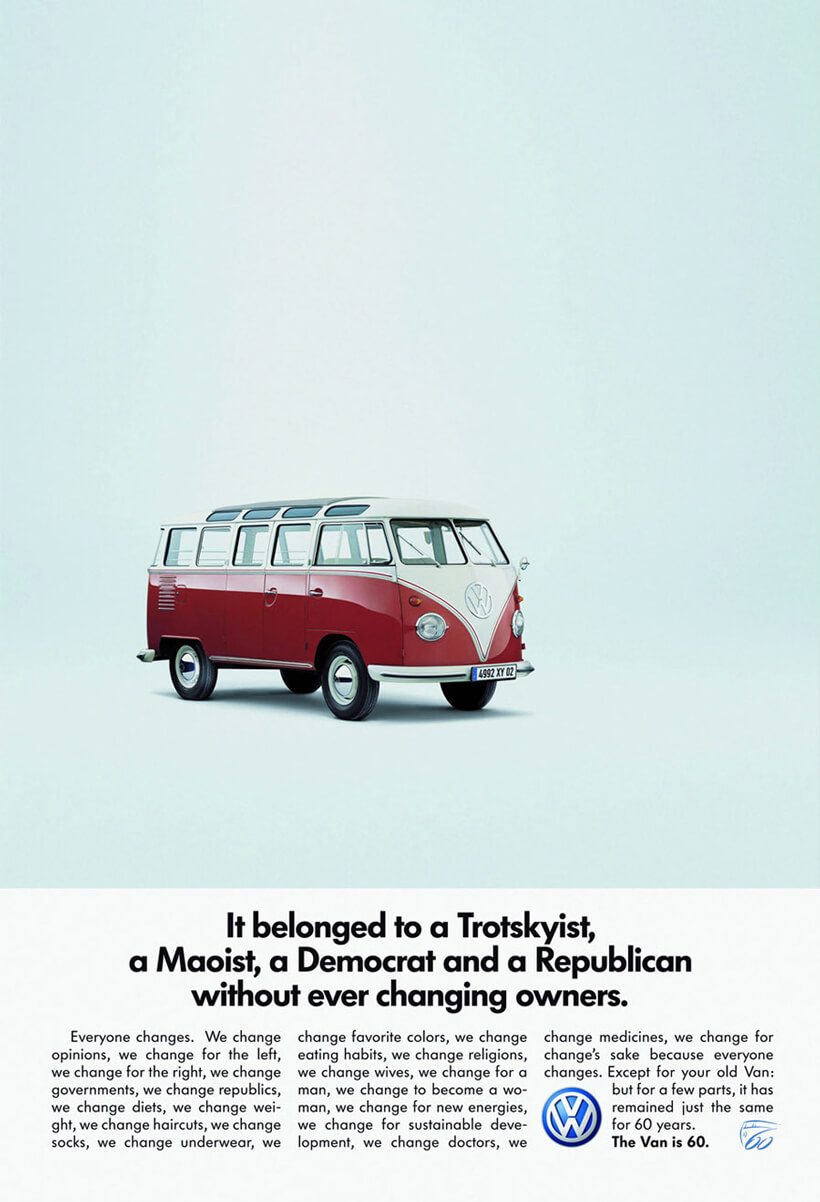

There was a nice Volkswagen print ad a few years back that captured this phenomenon. The art direction was simple, in that classic VW style, showing a three-quarter image of an old but cared-for VW campervan. The headline read: “It belonged to a Trotskyist, a Maoist, a Democrat and a Republican without ever changing owners.”

The charm was in the truth – the insight that certain objects can be not merely continuously owned but continuously loved through life’s upheavals, lurches and ideological elisions.

The charm was in the truth – the insight that certain objects can be not merely continuously owned but continuously loved through life’s upheavals, lurches and ideological elisions.

These are “life brands” – the ones that make sense to you and reflect something of your identity back to you even as you morph into all the people you once vowed you would never be. Coca-Cola has what it takes – as apt in the gnarled hand of a septuagenarian today as it was in the hands of the kids on that sing-along hill. Virgin pulls off the trick for some of its sub-brands. Evian, McDonald’s, Converse and Swatch are all contenders.

The defining characteristics of life brands are simplicity and authenticity. They don’t change too much and don’t actively seek to adapt to the character meanderings of even loyal customers. That VW ad itself was a celebration of the virtually untouched design and technology of a 60-year-old product in a world where change is all about.

As with all desirable brand typologies, there are fakes – brands that set out to be with you for the duration by planning a course on your behalf.

Financial services are always at it: “For the journey,” Lloyds Bank says, but it’s more a reflection of its own selfish ambitions – plotting your route through its preordained segments – rather than being there for you, whichever strange way you may turn.

Financial services are always at it: “For the journey,” Lloyds Bank says, but it’s more a reflection of its own selfish ambitions – plotting your route through its preordained segments – rather than being there for you, whichever strange way you may turn.

In any case, it’s hard to be a life brand in a loveless category. Banks and insurers may succeed in keeping your custom through inertia, but the distinguishing bond of affection will never be there.

The most remarkable feat of genuine life brands is to foster their appeal across two distinct temporal dimensions. They work longitudinally – partnering a cohort through its messily sequential phases of life. But they combine this with the horizontal plane, appealing to people at each of those different life stages today, from student to retiree and all the way stations in-between.

In that second capacity – and without getting too carried away with this – life brands serve some kind of social purpose at times when the generations seem never to be far from each other’s throats. Since their success is rooted in ubiquity rather than segmentation, they bring a little cohesion and wholeness to our daily interactions.

We can’t take this thinking too far. A 20-year-old horrified by the isolationist vehemence of an ageing Brexiteer will not be mollified by the consumption quirk that they both like the same cola. But it is a small connection, a gentle reminder that these two people are not from different planets, a little light adhesion in the societal cracks.

Life brands are still just brands – nothing more substantive than that – but, in these choppy times, where two UK polls within a year have exposed deep fissures between the generations, they are at least more part of the solution than the problem.

Two polls in less than a year have exposed deep divisions between the youngest and oldest voters in the UK.

According to Lord Ashcroft’s post-general election age-breakdown poll, the Conservative vote skewed violently up the age scale, with 38% of its entire vote coming from the over-65s and just 2% from the 18-24 group.

Labour attracted far more younger voters but its support was not confined to them: its vote was much more evenly distributed, with 20% coming from the 35-44 group versus 11% for the Conservatives.

According to YouGov, in the European Union referendum, 71% of 18-24s voted to remain compared with 36% of over-65s.

In a Guardian piece about people too young to vote in the referendum, a 17-year-old commented: “I feel I’ve been let down by an older generation who won’t be affected by the volatility of these decisions.”