No clear line of insight

Consider the following phrases: “When your clothes look good, you feel good”; “I prefer my kids to eat healthy snacks when they get hungry between meals”; and “The good thing about flying is the way it brings families and people together”.

If you said any of these things in conversation, you would know you were making the kind of routine observation that tends to get heads nodding. They would be platitudes; comfortable, uncontentious thoughts that oil the wheels of social interaction.

If, on the other hand, any of these statements were played back to you by a market research firm, after months of engagement with consumers, they would be packaged with much greater significance and dignified by a much loftier term. They would be insights.

Research agencies used to be content with diligently providing ‘findings’: useful, occasionally revealing, always grounding reports of what consumers were thinking, or how they were actually using products and services.

Marketing teams, combining data from different research episodes, would parlay these findings into ‘learnings’ – general principles to guide marketing and communications decisions.

However, it seems that this is no longer enough. Virtually every research agency talks about insight generation. One or two have even stretched the noun into a verb to describe their core activity as ‘insighting’.

What they don’t do, in the main, is define what an insight is, or how it differs from an observation or finding. So full marks to GfK, which, while admitting a definition is far from easy, has at least had a go: “Insight is a breakthrough of understanding with the potential to drive change.”

You can understand the desire of research companies to add gloss to what they do. Why merely probe, research or reveal when you can ‘insight’? Why charge for mundane findings when you can add value through something far more precious?

For marketers, though, the trend is disquieting in two connected ways. First, most of the claimed insights are nothing of the kind. I have seen all three of the platitudes quoted at the start of this piece presented as insights, with the ‘feel good’ one appearing in several versions across various categories: ‘When your hair/skin/make-up looks good, you feel good.’

These are simply findings or observations. Human beings are rarely terribly surprising, so consumer research alone is unlikely to provide the breakthrough flash of revelation that justifies the term ‘insight’.

The second worry derives from the first. If insights don’t come naturally out of the research, someone has to inject some imagination to create them. But is a research company the best place to find this? Insights worthy of the name generally arise from a collision of ideas, so they are more likely to be discovered by people with an overview of disparate data sources and other cultural, market and brand factors.

There is something else. The exuberant growth of the insight industry, with its roots in the soil of research exactitude, has encouraged the belief that insight generation is the only path to marketing excellence.

But is it? Sometimes that breakthrough revelation just won’t be there, but empathy, product superiority, clever innovation and good communications can still ensure a competitive edge. That, and an impassioned brand belief: insights, even surprising ones, are no substitute for vision.

In a study undertaken in 2003, US academic Mohan Sawhney, of the Kellogg School of Management, defined consumer insight as ‘Fresh and not yet obvious understanding of customer beliefs, values, habits, desires, motives, emotions or needs.’

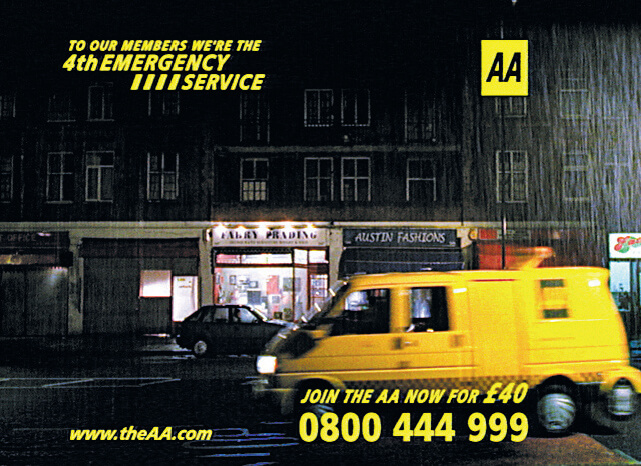

The AA motorists’ panic inspired brand positioning

Sawhney observed that insights are often discovered purely by accident, can be rooted in anomalies and ‘rarely emerge from quantitative analysis’.

Consumer insights often emerge from unusual sources. The AA’s famous ‘4th emergency service’ positioning was devised by the ad agency after it listened in to calls from stranded motorists, and noted the sense of panic in their voices.

In 2006, UK planner Simon Law analysed the award-winning ads at the Cannes Lions festival over a six-year period, and came to the conclusion that only 17% were based on a true consumer insight. The remaining ads were rooted either in product facts or cultural trends, or were seemingly random.