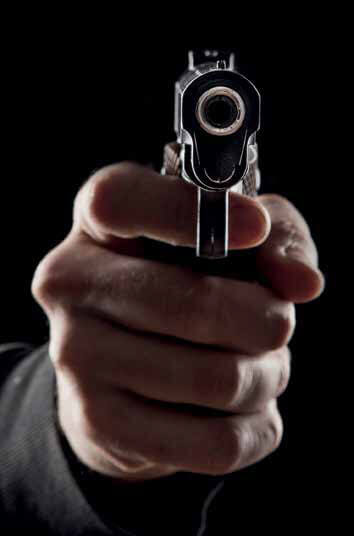

Ready, fire, aim

In a recent talk at London Business School, Gary Hamel posed the question: “How do we infuse every organisation with the spirit of entrepreneurship?” It was, he said, the “question every business should be asking”.

Should they? Should you? Entrepreneurship is one of those loosely sketched notions that sounds good and exciting and wholly positive in theory – especially coloured in Hamel’s terms: “Bold, simple, lean, open, flat and free.”

In practice, some less desirable characteristics tend to come into the picture: volatile, selfish, bloody-minded, impatient, insular.

Be careful what you wish for, in other words. So before you try to work out how you should bring this combustible force inside your organisation, it might be apt to ask yourself why.

Could the spirit of entrepreneurship help you achieve those ambitious objectives you and the team have set down? Ah, “objectives” – meat and drink of corporate life, anathema to entrepreneurs.

In her seminal study What Makes Entrepreneurs Entrepreneurial?, Saras D Sarasvathy, of the University of Virginia, drew a distinction between the “causal” thinking patterns typical of managers and the “effectual” reasoning of entrepreneurs.

Good managers select the best of several available routes to the desired, agreed goal – or, if they’re imaginative, create new ones. That’s causal thinking. Entrepreneurs, with their effectual rationality, don’t bother with an objective at all but start with a set of circumstances and imagine a range of potential endpoints from there. You won’t know which one they’ll run with because they won’t know either, at first.

Let’s try something else. Could entrepreneurship – “simple, lean” – help clear impediments from your daily path? Is that streak of ruthlessness exactly what you could do with to blast a way through the problems and people that seem to be holding you back? In fact, as Sarasvathy shows, entrepreneurs don’t resist roadblocks: they welcome them and use them to reshape their thinking. So, just as you thought you’d got with the plan, it changes.

OK. Could entrepreneurship simply help you speed up processes a bit? This is like being in the centre of town and wishing you could get to the airport a bit faster. The entrepreneur is the equivalent of the intrepid biker without a helmet who will give you a lift on the back. It won’t be “a bit faster”, it will be way faster – but maybe you won’t get there at all. The impatience of entrepreneurs is scarily fused with their high tolerance for risk.

OK. Could entrepreneurship simply help you speed up processes a bit? This is like being in the centre of town and wishing you could get to the airport a bit faster. The entrepreneur is the equivalent of the intrepid biker without a helmet who will give you a lift on the back. It won’t be “a bit faster”, it will be way faster – but maybe you won’t get there at all. The impatience of entrepreneurs is scarily fused with their high tolerance for risk.

They bypass research, shun competitor analysis and will often sell to customers ahead of building the product, adjusting on the fly. As one of Sarasvathy’s serial entrepreneur respondents put it: “I always live by the motto: ‘Ready, fire, aim.’”

In businesses accustomed to risk management, imbued with an ethos of team-play and always seeking to make sense of the future, the presence of the full-blooded entrepreneur is felt as an assault on the system.

And there is not really any other kind. If there is a flaw in Hamel’s reasoning, it lies in that idea of “spirit”, as though you can take on a safe sample, a dilute mix, a hint of the real thing. But entrepreneurs are all-or-nothing diehards. It’s illogical to think you can grab just a bit of the total commitment that characterises them.

If we’re not careful, “entrepreneurship” will become one of those conveniently blurry terms that serve the purpose of relieving us from the burdensome duty of having to think hard about the specific problems we face.

Most businesses need to find ways to be faster, more courageous and more inventive. The hard part is seeking and implementing practical strategies to make that happen. Sweeping them up in the catch-all concept of “entrepreneurship” is lazy and unlikely to inspire meaningful change.

That said, there will be those managers who want the full-blooded thing, understand the implications and buy into Hamel’s vision of the reward: “owning a part of the future”.

How should they encourage the potential entrepreneurs in their own organisations? How should they clear a path for them? The answer, of course, is that they shouldn’t. They should keep the barriers high, keep the funds at arm’s length, keep the logistical support at baseline. If the budding entrepreneurs really are the right stuff, they’ll find ways to overcome those odds.

At which point, it’s a case of deciding you’re up for the ride, fastening your seat belt – and hoping that Hamel is right.

Professor Gary Hamel

The visiting professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at London Business School is the most reprinted author in the Harvard Business Review and has introduced many of the managerial concepts regularly bandied around the boardroom, including “strategic intent”, “core competence” and “management innovation”. He lives in Silicon Valley – spending time with the entrepreneurs he encourages big business to emulate.

Professor Saras D Sarasvathy

Sarasvathy is a member of the strategy, entrepreneurship and ethics group at Darden School of Business, University of Virginia. A leading scholar on the cognitive basis for high-performance entrepreneurship, she introduced the “theory of effectuation” – a set of decision-making principles that helps entrepreneurs identify opportunities and create value. Unlike most academics, she has also founded and run several businesses.

Luke Johnson

As a founder of Risk Capital Partners, Johnson backs entrepreneurs; as a columnist for The Sunday Times, he frequently writes about them. He has also been one – most notably with Pizza Express, which he took on with just 12 restaurants and grew to more than 250. In 2013, he created a think tank – The Centre for Entrepreneurs – that aims to promote the role of entrepreneurs in creating economic growth and social wellbeing.