The marketers’ complaint

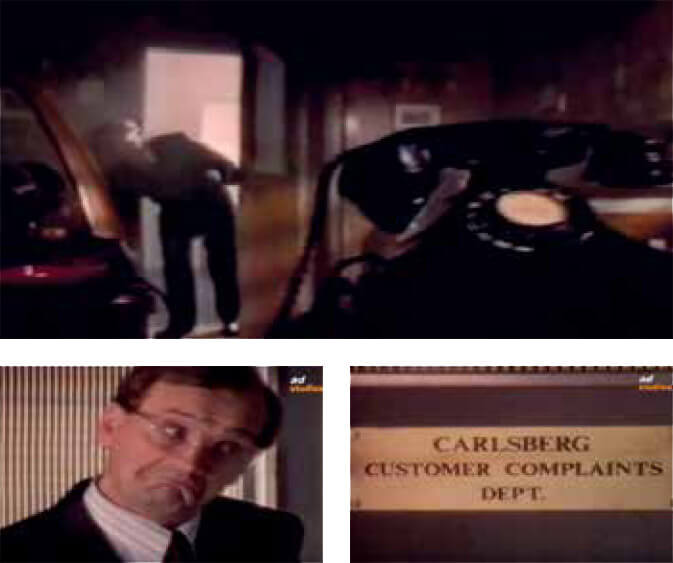

Twenty-odd years back, there was a Carlsberg commercial, an early one in the “Probably” campaign, that showed an executive walking along the corridors of a modern office building becoming distracted by the sound of a constantly ringing phone.

He slows down, then pauses; the phone goes on ringing, from inside an empty office. So he goes in and answers it, blowing away cobwebs from the desk and dust from the receiver, which clearly hasn’t been used in ages, and it turns out to be a wrong number. When he comes out of the office, we see the sign on the door: “Carlsberg customer complaints department”.

I worked on the Carlsberg account in those days, and that commercial always got the highest recall scores, so we ran it every year. The actor who played the executive probably retired on the repeat fees. Was everything about Carlsberg so perfect that there was never the hint of a complaint? Probably not. But this was customer satisfaction seen through a marketing department’s misty lens and, hey, it was just an ad, so it wasn’t meant to be taken seriously.

A lot has changed since then, but the means by which customers are expected to register their dissatisfaction has not. There are still such things as “complaints departments” – often a sub-branch of customer services – through which these tiresome intrusions are meant to flow, or to which they are “escalated”. Customers still predominately use calls to complain and, like the Carlsberg phone, these often feel like they are playing to an empty, uncaring office, where you’ll be lucky to get an answer before next Pancake Day.

And marketers still have a misty view of the whole process – something that happens “over there”, handled by people with long tethers and thick skins, while we get on with the serious business of making ads to attract new customers.

Where that leads is to the salutary tale of Vodafone, fined recently by Ofcom not merely for charging customers for services they never received but for failing to competently handle the ensuing torrent of complaints. The regulator reported that many customer-service agents were not even clear on “what constituted a complaint”. Hint: when the person on the other end is manifestly apoplectic and making wailing sounds like a wounded dog, it probably isn’t to pass comment on your new Christmas ad. And it unfortunately isn’t a wrong number.

Meanwhile, where were the Vodafone marketers during this time? Working on the next “Power to you” spot, perhaps, tweaking and finessing while their powerless customers hung on and called back again and again, listening to the stupid elevator music and getting madder and more crazed at the knowledge that the very object of their ire was racking up money on their futile call minutes.

The frustration of unanswered or badly managed complaints is a combustible force. And here’s something that has changed over the past 20-plus years: today, there is the fuse of the internet and the spark of social media with which to detonate it. An academic study has shown that when the route to complaint-handling is complex, people are more likely to vent on review sites or Twitter and wreak far greater public damage.

The frustration of unanswered or badly managed complaints is a combustible force. And here’s something that has changed over the past 20-plus years: today, there is the fuse of the internet and the spark of social media with which to detonate it. An academic study has shown that when the route to complaint-handling is complex, people are more likely to vent on review sites or Twitter and wreak far greater public damage.

Apathy in the face of customer unrest is the marketers’ complaint, and it’s time we found a cure. We need to see complaints as another brand touchpoint, and a crucial one at that, which means wresting the process out of whatever corner of the organisation in which it is housed now and taking it under our wing.

I know of only one chief marketing officer who has done that and, as she works for one of our larger banks, it is an even gustier act than it first sounds. But as she puts it: “How else can I know what consumers really care about?”

Our aim should be twofold. On the one hand, we need to make it far easier for customers to complain – opening up new digital channels, putting a “red-hot angry” button on the website, creating priority lines; on the other hand, we need to make it far harder – by tackling and fixing the things that get them riled in the first place.

To do that, we need to hear what they are saying first-hand. Why shouldn’t every marketer in the organisation be assigned to take and follow through on a fixed number of customer complaints each week? The pushback will be that this will take time off other work, make them late for big meetings and perhaps compromise that vital board paper. But that’s what our customers go through when they are put on hold. If we feel their pain, it will be the best incentive to ease it.

It’s time for marketers to blow away the cobwebs and dust from our Byzantine internal complaints systems and take the issue of customer dissatisfaction far more seriously. Consumers will find a way to punish us if we don’t – no “probably” about it.

Vodafone ran into deep trouble with the communications regulator, Ofcom, last month for “serious and unacceptable failings” involving “mis-selling, inaccurate billing and poor complaints procedures”.

The company had taken money from 10,452 pay-as-you-go customers between 2013 and 2015 but not credited anything to their accounts.

Ofcom punished Vodafone with a record £4.6m fine, made up of two separate amounts: £3.7m for taking customers’ money and not providing a service, and £925,000 for bungling the complaints – which took almost 18 months to sort out.

Vodafone blamed migration to a new IT setup and said that it deeply regretted the failures, admitting that it had not done its best to “meet customers’ needs”.