The personality puzzle

When marketing teams craft their brand-positioning models, there are always tough bits, thorny bits and fun bits.

At the tough end of the spectrum is that box that sits there like a conscience: ‘Reasons to believe’. Unless the moderator is exceptionally lax, phrases like ‘world-class capability’ will be captured only with reluctance, as a spur to press on for something more concrete.

‘Target audience’ can be thorny, eliciting a tussle between those whose mantra is ‘target narrow to catch wide’ and those whose tendency is to target pretty much the whole world.

‘Proposition’ is the big one, and feels like it – a sweaty session that is frequently both tough and thorny, as teams struggle to pack all the brand virtues into a tight, motivating brand phrase.

Often the decision is taken not to ‘wordsmith’ the proposition further in the group, but appoint a smaller team to develop it later, after the thought-starters. This is a sensible call, but one that leaves the group with a feeling of coitus interruptus. Just as well, then, that there is some light relief coming up in the shape of ‘brand personality’.

Now the team can unwind and indulge in an outpouring of the adjectives it feels best capture the spirit of the brand. ‘Vibrant’ is always up there; ‘confident’ is rarely far behind. The upbeat words cascade with such exuberance that whoever is at the flipchart can barely keep up.

Too many? Never mind, they can be themed to produce a catchy header, working in a kind of opposition: ‘playful leader’, perhaps, or ‘pragmatic visionary’. Better still, the adjectives can find embodiment as a real personality: Ruby Wax! Angelina Jolie! Nelson Mandela!

If only there were a positive correlation between enjoyment and utility. Instead, in the real world, the statements in that ‘personality’ box can seem out of step with the brand people know.

Adjectives that felt right in the group suddenly assume all the credibility of a pasted-on smile. The two-pronged headers behave as the oxymorons they are. And when you’re, say, designing a shelf wobbler for your floor-cleaner brand, its association with Nelson Mandela can seem tentative.

The way to produce a more realistic statement of brand personality is to come at it with more rigour – which, unfortunately, means less fun. If you’re serious about getting it right, Jennifer Aaker’s Brand Personality Framework is the academic tool to reach for.

Aaker’s central insight is that the dimensions of brand personality must include some that humans desire but do not actually possess – which is one reason why interpreting brands as real people is misguided.

Her greater contribution has been to take one of the most ephemeral aspects of marketing and subject it to measurement. The framework plots five brand personality dimensions: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication and ruggedness. Each of these is broken down into a set of facets: ‘sincerity’, for example, comprises down-to-earth, honest, wholesome and cheerful. Each of these, in turn, is divided into several traits, which can be gauged on a one-to-five scale for any brand.

Aaker’s framework offers teams an empirical way to come at the personality of a brand. Even if the aim is to develop that personality, it at least gives a grounded assessment of what you’re moving on from.

It turns out that getting brand personality right is like everything else in marketing: hard thinking, hard choices – and hard work.

Jennifer Aaker is the General Atlantic Professor of Marketing at the Graduate School of Business, Stanford University.

She has a PhD in marketing and a PhD minor in psychology. Her courses include ‘Designing happiness’, ‘How to tell a story’, ‘Building innovative brands’ and ‘The power of social technology’.

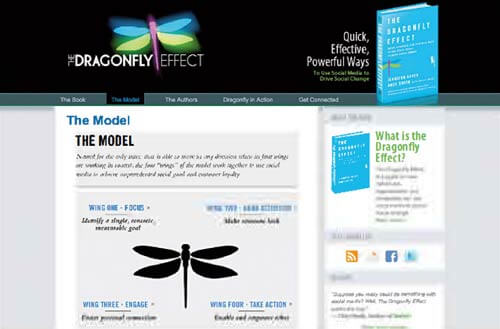

The Dragonfly Effect Aaker’s book looks at the use of social media to drive change

Her academic research into brand personality has been followed by new work on ‘time, money and happiness’, focusing on questions such as: “What actually makes people happy, as opposed to what they think makes them happy?’

Her most recent publication, The Dragonfly Effect, cowritten with her husband, Andy Smith, is a guide for how individuals, organisations and companies can use social media to propel social change. It was inspired by the story of a group who used social media to find a bone marrow donor for a friend.

Aaker’s father is David Aaker, Emeritus Professor of Marketing at Haas Business School and co-author of bestseller Building Strong Brands.