The price of purpose

When a think tank called Big Innovation Centre spends a year pondering how UK business can be more competitive, you expect some bold, new thinking. The panel, chaired by Will Hutton and advised by heavy-hitters from Unilever, GSK and the Bank of England, among others, issued its “interim report” last week.

Its conclusion is neither new nor bold. It is that companies “should have a corporate purpose”. They should craft a “statement of what they stand for” and “define their contribution to society”. Really, that’s it.

Modern marketers will be pleased to find endorsement for something they’ve championed for decades now, but puzzled to see it presented in the guise of “innovation”. Purpose is one area where marketing has led business thinking, with those closest to consumers and employees conscious of the need to inspire people beyond a transactional level.

Perhaps sensing the lack of newsworthiness in its declaration of the age of the “purposeful business”, Big Innovation Centre did what think tanks always do and concocted a Really Big Number to capture headlines. Journalists duly reported that the tardiness of British companies to declare a purpose could cost the UK economy “up to £130bn a year”.

It won’t. The figure is the product of baroque extrapolation from other reports that attempt to quantify the commercial value of a range of variables – from CSR programmes to “customer satisfaction” – without isolating purpose itself. And it succeeds in reaching that giddy £130bn only through further leverage to market capitalisation – which isn’t something that accumulates “per year”.

More troubling is that the panel felt the need to reach for a financial measure in the first place. Here is a report that – rightly – seeks to raise the sights of those who run corporations, and to promote social purpose as a higher-order ideal that should stand above shareholder return. What one metric does it offer as an incentive to those who have not yet seen the light? Stock-market capitalisation.

Paraphrased, that would look like this: “We believe it’s time for UK business to put purpose before profit. Why? Because if they do, they’ll make more profit.”

Paraphrased, that would look like this: “We believe it’s time for UK business to put purpose before profit. Why? Because if they do, they’ll make more profit.”

The report thereby skirts the most essential, and least palatable, truth about corporate purpose – its sacrificial nature. While it is just possible that a trenchant, honoured purpose will achieve pay-off for your brand sometime deep in the future, it is a certainty that it will exact a cost in the here and now.

That cost usually comes in the act of forgoing tempting business opportunities to grow share or trade in an adjacent sector, if they happen to run counter to what you believe about the world.

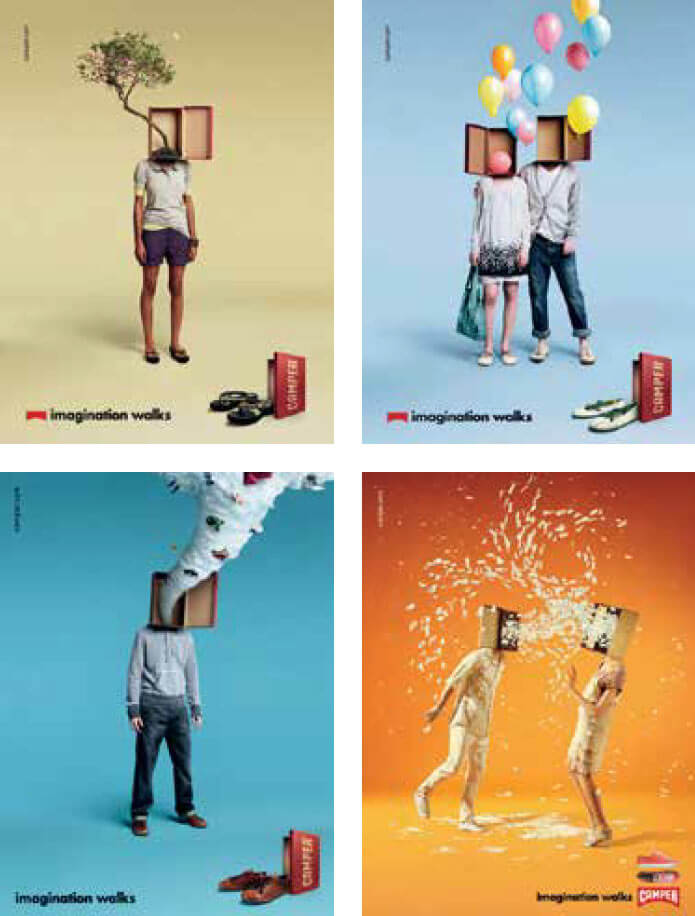

An example is the shoe brand Camper, which has one of the sweetest purpose statements out there. The brand was founded by a fourth-generation shoe-maker, Lorenzo Fluxá, who believes in the virtue of “slowness”. He counsels us to slow down to walking pace in our hectic, modern lives and take in the wonder of the world around us.

The Camper statement of purpose is to “Provide the safest and cheapest vehicles possible: comfortable shoes”. That’s why the brand hasn’t extended into trainers – all about speed – and why it won’t get into fashion heels that hurt. Sales would be higher if Camper exploited its fame in those sectors, but purpose intervenes to block that route to riches.

Big symbolic gestures with the aim of underlining purpose to employees are also more credible if they involve commercial sacrifice. Last year, US retailer REI closed all its stores on Black Friday – the busiest shopping day of the year – to publicly emphasise its belief that life is better lived outdoors (see panel).

Putting purpose first is a nobler way to do business but is not for the fainthearted, and certainly not for those fixated by market cap.

What we need is a better metric to capture the mix of social and financial contribution that modern businesses make in the world – an index that condenses profitability with the sacrifice of standing by principles.

If Big Innovation Centre could use its brains to devise that, and its influence to get it universally accepted, it will have served some purpose.

Black Friday is the busiest US shopping day of the year, accounting for sales of $10.4bn in 2015. Yet outdoor-wear retailer REI closed its stores for the day, suspended ecommerce and gave its 12,000 employees a paid day off to encourage them to embrace the great outdoors.

The brand’s stated belief is that “a life outdoors is a life well lived” and it sought to encourage consumers as well as employees to abstain from the “madness of Black Friday”, crammed inside malls or shopping online.

The big symbolic gesture was backed by a microsite, social elements and a communications campaign with the tag “#OptOutside”. One film showed chief executive Jerry Stritzke imploring viewers to join the “Opt Outside” movement as he sat at his desk – which turned out to be located on a stunning Washington State mountainside.