The trouble with trust

It’s simple enough to put ‘trusted’ in your brand codification. I see it a lot, often in the form: “Vision: to be the most trusted brand in (category here)”.

What’s less simple is for consumers to answer the question: “Do I trust this brand?” The reason this is far from straightforward is that it is not a single question, but two – the answers to which often pull in opposite directions.

That’s the trouble with trust: one taut syllable that trips off the tongue, then confounds you with its slippery bifurcation. What are those two branches of meaning?

The first is to do with intentions: “Do I trust this brand to exercise commercial restraint, to put citizenship at its heart, to pay its taxes and behave in an ethically responsible way?”

The other is all about capability: “Do I trust this brand to know its stuff, deliver on its promises, overcome obstacles and bring me the products and services I want?”

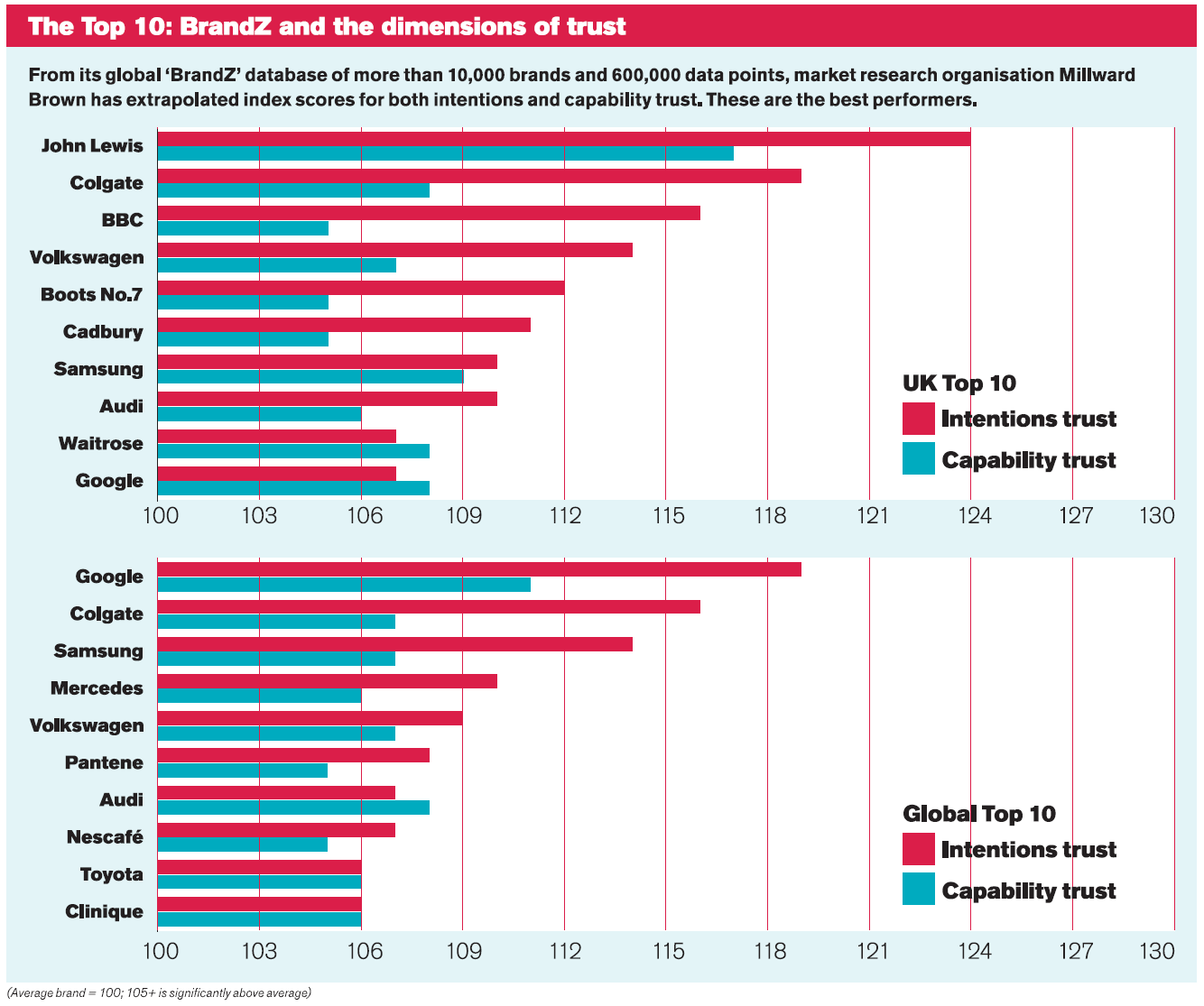

Intentions trust, capability trust – often with an extraordinary gulf between them within the same brand.

Do people in the UK trust Amazon, for example? Answer: no and yes. It’s hard to be confident about its good intentions when its managers wriggle in front of a televised Public Accounts Committee for trading through a Luxembourg subsidiary in order to reduce UK taxes to 0.1% of revenue.

BBC Question Time audiences can be reliably whipped into a frenzy by the mention of Amazon – along with Starbucks and other serial offenders – getting away with tossing peanuts at the Exchequer when “hard-working families” are having to dig deep to make their contribution.

When it comes to capability, though, Amazon can be trusted to get it right time and again. It’s a fantastic machine that can pitch a feminine hair trimmer or a three-port lever cage clamp terminal block to your door dependably by 10am tomorrow when you order tonight.

What Amazon shows is that people will do business with brands they don’t trust – just so long as it is intentions, not capability, that is the weaker branch. Despite all the righteous indignation, its business in the UK has surged 40% year on year since the tax scandal broke.

Consumers aren’t so kind to ‘yes-no’ brands – where intentions get the nod, but capability is doubted. The term they will use, when you’re conducting groups about ethical deodorants or sleepy building societies, is “well-meaning”. They admire, but don’t buy – at least, not in the numbers that would threaten the more professional players.

The Green Party is a graphic example of this. Who can doubt that, relatively, if not absolutely, its politicians have noble intentions? Its capability, by contrast, looked flaky even before leader Natalie Bennett struggled with basic economic questions in a radio interview. The one council it runs – Brighton – ranked 306th out of 326 English councils for its recycling rate.

What about the other two possible combinations in our ‘trust’ version of the Boston matrix: no-no and yes-yes?

Brands that are negative on both ‘intentions trust’ and ‘capability trust’ will be scarce for obvious reasons. That said, RBS came perilously close to defining this quadrant in 2012, when the lamentable intentions trust it shared with the other big banks was compounded by an IT fault that prevented 12m people from accessing their own money.

High levels of trust for both intentions and capability is the combination that many aspire to, but few achieve. The best example is John Lewis (see panel) which does what it does superbly well, shares the rewards with its employees and exudes a sort of all-round decency.

In there is a clue to why this high ground is worth the assault, even though the more cynical ‘Amazon’ space can still bring in the money. In the end, it’s not just consumers that count, but employees, too: they want to work for a brand that uses its talents to do a bit of good in the world.

Don’t we all? Which brings us back to that brand codification. If you’re serious about ‘trust’ – in both its guises – you could do worse than reduce your brand model to just two boxes: What do we believe? What are we going to do about it?

Trenchant answers to both, and an iron resolve to honour them, will earn you that most precious and elusive of brand perceptions, and all the rich rewards that come with it.