The vital vulnerability

For the duration of the 2012 Games, the International Olympic Committee will enforce what it calls a “clean stadia policy”. This means that inside any arena in which an Olympic event takes place, there will be no corporate branding whatsoever.

In the specially commissioned complex at Stratford, this has been straightforward enough to arrange. It is another matter, though, in the numerous pre-existing venues that will host Olympic events, which include Wembley, Lord’s, Old Trafford and Brands Hatch.

So specialists have been contracted to audit these venues and identify where brand marks are now, in preparation for their removal later. The audit will be sufficiently thorough to pinpoint even the logos of manufacturer brands glazed into the ceramics of urinals. If these cannot be easily erased, they will be hidden from the eye with masking tape. Clean means clean.

It is an irony, therefore, that the plan to allow an exterior sponsored “wrapper” on the main East London stadium has engulfed the Olympic movement in the fallout from the dirtiest corporate catastrophe of modern times: Bhopal.

The sponsor of the wrapper, at a cost of £7m, is Dow, one of the world’s biggest chemical manufacturers and already an Olympic supplier. The controversy arises from Dow’s purchase, in 1999, of Union Carbide, owner of the pesticide plant in India that in 1984 spewed out poisonous gas, resulting in the deaths of more than 4,000 people.

The sponsorship plan unleashed a media storm culminating in the resignation of Meredith Alexander from the Commission for a Sustainable London 2012, who vows to support families still lobbying for the case to be reopened.

As these brands will attest, the jeopardy is real. Whatever the instigating event results from, it can take decades for trust to be restored – if it ever is.

Nestle, infant formula scandal: It is almost 40 years since NGO War on Want published a report entitled ‘The Baby Killer’, exposing Nestle’s promotion of infant formula over breast milk in the developing world. The company has struggled to overcome the stigma ever since.

McKinsey, Galleon Case: Global managing director Dominic Barton ventured that it could take 20 years for McKinsey to re-establish its credibility after one of its senior managers pleaded guilty to insider dealing in the high-profile 2011 trial.

BP, Deepwater Horizon oil spill: BP initially sought to deflect blame for the 2010 environmental disaster onto its supplier, Transocean. Faced with the decimation of its own brand, the business swiftly adopted a more contrite position, which culminated in the resignation of its chief executive, Tony Hayward.

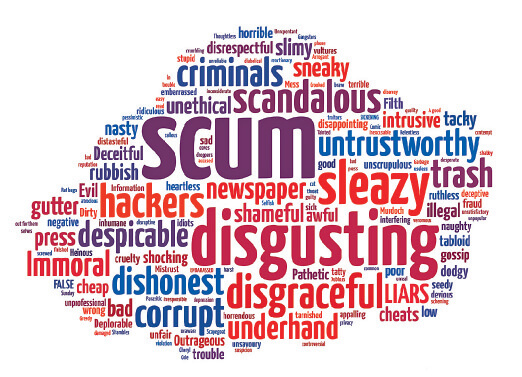

NOTW scandal Public reaction in 2011

News International, phone-hacking: The scandal led to the closure of the UK’s bestselling newspaper last July, compelled the Murdochs to appear at a public inquiry and put paid to NewsCorp’s bid for full ownership of BSkyB.

When one business buys another, what does it acquire? Along with the capability, people, plant and customers, it takes on less quantifiable phenomena – reputation, heritage and accountability. In short, a brand.

Such controversies serve to remind us how brands came about in the first place, and the purpose they really serve. Their genesis dates to a time when people were regularly cheated by shifting and unaccountable traders. Dirty practices included adding water to butter, chalk to flour and sand to sugar – along with routine cheating at scales.

Then, more upright individuals and groups, often driven by a common morality such as that of the Quakers, developed enduring trade names and marks that came to symbolise their commitment to fair dealings.

Brands established trust. How, exactly, though? Through jeopardy. It is the vital vulnerability at the heart of the corporate mark, without which the whole edifice of branding would be meaningless. The public knows that the brand owner has invested in its reputation, symbolised it for all to see, and has a great deal to lose by being at fault. Potential loss by one party is key to the trust of the other.

Dow’s misjudgement is not to seek to sponsor the Olympic ideal. To be publicly visible and seen to invest in your corporate presence is what good brands do. The error lies in that choice of words: “Dow was never there.” Then who was? For reasons that suited its corporate balance sheet at the time, Dow swallowed Union Carbide’s assets and jeopardy, both, in 1999. It cannot seek now to apply masking tape over Bhopal.