Passion Brands:

The Extraordinary Power of Brand Belief

WHAT IS A BRAND FOR?

The commercial answer to that question is both simple and well-rehearsed. It is to achieve the potential for a higher value in the minds of consumers than the generic, unbranded product, or service. Numerous brands in virtually all categories have demonstrated this power at work. Evian costs more than the commodity that emerges from the tap; Dove persuades us to part with more for its bars than we would for good but unbranded soap; even where the formulations are identical, branded consumer medicines such as Nurofen can sell for many times more than the generics. A brand – the leanest definition of which is “a product or service, plus values and associations” – enjoys a value pull over mere products and services in which values and associations are either absent or weak.

Still, this gets us only so far, since most brands do not compete exclusively with generic products or services. They tend to compete with other brands. Tall trees may enjoy a greater share of natural resources than pygmy trees, but this is not such an overwhelming advantage in a forest of tall trees.

That gives way to a second question. How can any given brand earn advantage over other brands? How can this tree grow a little taller than the other tall trees? Again, the answers are well-rehearsed but they are not so simple, at least, not in practice. Advantage may be pursued by means of a whole range of disciplines and activities: consumer understanding, innovation, segmentation, new distribution channels, bundling, packaging, design, communications, service initiatives, pricing and more.

The problem with this list is not that any one of the tasks is superfluous but that all of them are necessary just to keep up, let alone forge ahead. Branded competitors will be engaging in each and every one of these disciplines and actions, at the same time as you are, in order to gain advantage over you. It is actually worse than that; not only will they be doing much the same things, but the outcomes will also tend, in any single category, to converge on much the same answers. Brands will arrive at similar understanding, devote time and money chasing similar innovations, and employ similarly brilliant agencies to devise similarly ingenious communication ideas and media strategies.

This point is crucial to anyone seeking to differentiate their brand according to the latest fashionable doctrine. Right now, that doctrine is consumer insights. These are chased with enormous zeal by both brand owners and their agencies, deploying the latest research techniques to prise open new nuggets of revelation. But since those research techniques are available to all, and since consumers are likely to reveal similar glimpses into their souls irrespective of who happens to be asking, it is unlikely that you will end up knowing anything your competitors don’t.

Convergence among brands within a category is almost as inevitable as convergence in the height of the tall trees of the forest. You cannot shrink back from toiling at the list above – since to do so will stunt your brand’s ability merely to keep up – nor can you expect it, except in the rarest circumstances, to lead to lasting advantage. What it leads to instead is the mall-like world of “consumer-led brands,” in which consumer needs are met in predictable ways by brands whose quirks and rough edges have been erased as though they had been through a wind tunnel, which, in a sense, they have.

UNCONVERGE

Yet there is one element within your brand’s DNA that can promote divergence from other brands, one facet that is hard to copy because, often as not, it does not “present” to competitors an easy-to-spot advantage. (In fact, sometimes the very reverse: it can appear, short term at least, to be a disadvantage.) What is this elusive, mercurial, and apparently sacrificial quality?

It is belief. It is the reason for the existence of the brand in the first place. It is the idealism that moved somebody in the perhaps murky past to start the whole thing going, in spite of all the obstacles that would have needed to be overcome. For Henry Ford, it was a belief in freedom of mobility, with his vision to “open up the highways for all mankind.” For Pleasant Rowland, the founder of American Girl, it was a belief that better role-model “narratives” were needed for preteen girls in the ersatz world of Barbie-like dolls. For Luta’s Luke Dowdney, it is a conviction that martial arts can give young people the impetus to end gun crime in the favelas (see the panels later).

Now we arrive at a quite different answer to the question posed at the outset: “What is a brand for?”

It is for changing the world. It is for improving the lot of human existence. It is for making a small difference based on big convictions. This is the social answer, one that may lead to the commercial answer, and to advantage, precisely because it does not start there. In this paradigm, a brand is the embodiment of the expression used by the supply-side economist George Gilder in his book Wealth and Poverty (Regnery, 2012): “Capitalism begins with giving.”

That is how brands came about in the first place. Their genesis dates to a time when people were regularly cheated by shifting and unaccountable traders. Dirty practices included adding water to butter, chalk to flour, and sand to sugar, along with routine cheating at scales.

Then more upright individuals and groups, often driven by a common morality such as that of the Quakers, developed enduring trade names and marks that came to symbolize their commitment to fair dealings.

Many of those early belief-led brands prospered and are still forces for good today: Cadbury, Carlsberg, Clarks Shoes, Hershey, John Lewis, Krupp, Lever (now Unilever), Philips, Price Waterhouse and The Co-operative. On the other hand, the recent fate of Barclays and Lloyds – both originally Quaker banks – demonstrates what happens when the drive for gain is allowed to take precedence over the founding tenets of, in their case, “simplicity, honesty, and integrity.” Had they adhered to those foundational ideals, they would have better served not only their customers and the wider community, but also themselves.

Brand belief is a potent force. It doesn’t obviate the necessity for the normal watchful duties of good brand stewardship, but it refracts all the research findings, all the R&D ideas, all the service initiatives, product upgrades, and communications platforms through a powerful lens, one that focuses on a single question: “Is this true to what we believe about the world?” When the answer is “no,” the brand doesn’t go there, changes things around, remolds its offer to conform to its convictions, even if that means knowingly flying in the face of consumer wants and opinions. Belief is therefore the foundation of those much-sought-after brand qualities: character and authenticity, the hallmarks of what we will call Passion Brands.

Four questions typically ensue from this line of reasoning.

How Does Belief Confer Commercial Advantage?

Belief-led brands enjoy two natural advantages over brands that merely pander to the latest consumer whim. They inspire deeper emotional engagement among customers, and more impassioned commitment among employees.

Why should brand belief have the power to move consumers who, after all, might simply be choosing an aftershave or a canned soup? The answer takes us into the realm of self-identity, and the role that consumption plays within it. Over the past four decades, this has been the subject of intense research by the leading behavioral and psychological academics – a list that includes, but is by no means limited to, Aaker (J), Bauman, Belk, Elliott, Featherstone, Giddens, Ritson, Thompson, and Yi Fu Tuan.

Their body of work shows that people construct a “narrative of self” to help them navigate their lives and the world around them. A range of cultural resources can be used – consumed – by the individual to reinforce and calibrate this sense of self-identity. The available repertoire includes brands, which are a potentially vivid means of self-endorsement: “This is the person I am inside, and this brand helps me feel that.” Note that the point is not outward display – not “badge values” signaling status to others – but rather the internal whispering of self to self. The upshot is that all kinds of brands are potentially involved – even those kept out of sight from others in cupboards, handbags, or sports lockers.

The more authentic the brand – so the more it is held integral by a belief and a strength of character that ensues from it – the more potency it has as an artifact of self. People will orient toward these beacons of belief – or steer clear of them – but they are less likely to ignore them.

Strong, clearly articulated belief is also a motivator for employees, a constituency that Oxford University’s Richard Pascale likes to describe as “volunteers who decide each day whether or not to contribute the extra ounce of discretionary energy that will differentiate the enterprise from its rivals.” According to a study by the global quantitative research agency Millward-Brown, organizations with “a strong ideology” enjoy advantages in their ability to both recruit and retain the most capable people.

There is a caveat to all of the above. The belief must be genuinely held, and must be adhered to even when things get tough. Sometimes, this may imply commercial sacrifice. Such is life.

Is Belief Just for Certain Kinds of Brand?

Is it just for founder-led brands? Or just for brands in naturally “heroic” categories, such as business systems or healthcare? Or just for one-off “cult” brands, such as Harley or Apple?

The answers are no, no, and no. While founder zeal can be a great inspiration, it is not the only ideological source from which to draw. Category should be no barrier: even humdrum consumer sectors – cleaning fluids, insurance, pet foods – have their own heroism if you get beneath the surface, as Unilever has shown with its belief-led reinvigoration of Omo, Rinso, and Breeze. As for cult brands, too much has been written about Harley and Apple, such that their stories blind us to those whose paths have been subtler. It is time we hear more about brands like KY, with its belief in the importance of intimacy, or the UK beautycare brand The Sanctuary, with its belief that beauty and pleasure are mutually reinforcing – a trenchant counterpoint to the prevailing science-and-Botox trends.

Belief is for any brand where the imagination, courage, and sensitivity exist to see it through, along with the wisdom to recognize that commercial goals, can be more harmoniously achieved by prioritizing social ones.

Is a Passion Brand Simply a Brand with Belief?

It is not quite that simple, and it’s not hard to see why. Even so potent a force as belief would not do much for a brand whose other qualities were myopia, stubbornness, and introspection. It follows from this that while belief is a necessary component of a Passion Brand, it is not, alone, sufficient. Belief must accompany a deep understanding of people, and must be fused with the capability, confidence, and exuberance to make it relevant to their lives.

Passivity is not part of the Passion Brand make-up. The objective is not for belief to sit there as inert ballast at the center of the strategic brand diagram. Instead, it is an active force that exerts influence over everything the brand does and is. A Passion Brand’s constantly renewed feel for people, markets, and the deep, swirling themes of contemporary life is the feedback mechanism through which it ensures that its belief stays relevant in a protean world. The belief is steadfast and unchanging; the way it is manifested is dynamic and free.

Can a Passion Brand Be Created from the Basis of an Existing Brand?

Let us take this question to the extreme. Imagine a brand in a humdrum category, neither market leader nor fashionably small, with a choppy history, no living founder to galvanize the workforce, a so-so record of innovation, and a me-too current positioning. Can such a brand make the transition to become a Passion Brand, with an identity based on belief, a view about how to make a difference in the world, the exuberance to make it meaningful to consumers, and the willpower to make it happen?

The short answer is “yes.” The long answer takes the form of the Passion Brand strategic methodology which we will now go on to describe – a process that is rigorous, proven, potentially thrilling, but not for the fainthearted.

DEFINITIONS

Brand

A product or service plus values and associations.

Consumer-led Brand

A brand that habitually uses the findings of consumer

research for direction, not illumination.

Brand Belief

The brand’s take on the world, a view on what would

make the world a little better, and how the brand can

work toward making it happen.

Passion Brand

A brand with a clear belief, a deep understanding of

people, and the capability, confidence, and exuberance

to connect the two.

AMERICAN GIRL: A BELIEF IN LEARNING THROUGH PLAY

American Girl was founded in 1986 by Pleasant Rowland, a former elementary school teacher then in her mid-40s. The idea was born of two separate moments of revelation that had struck her over the previous year. In the first, accompanying her husband on a business convention in Colonial Williamsburg, she sat on a bench and reflected how badly children were taught history at school.

American Girl was founded in 1986 by Pleasant Rowland, a former elementary school teacher then in her mid-40s. The idea was born of two separate moments of revelation that had struck her over the previous year. In the first, accompanying her husband on a business convention in Colonial Williamsburg, she sat on a bench and reflected how badly children were taught history at school.

The second was shopping for dolls to give her nieces for Christmas, and finding herself horrified by the choice between Barbie and Cabbage Patch Kids. As she recounts, “Here I was, in a generation of women at the forefront of redefining women’s roles, and yet our daughters were playing with dolls that celebrated being a teen queen or a mummy.”

Rowland believed that preteen girls would become interested in history by identifying with dolls based on historic periods. She wanted to celebrate the active roles that women had played, so that today’s girls would not be persuaded to merely accept the roles society creates: “If we can make girls excited about history, we can inspire them to create history.”

Success was achieved through a combination of books that focused on life in a specific historical period – perhaps the colonial or depression years – and dolls with historically accurate clothes and accessories, with which girls could play out the stories.

The brand has always aimed to provide meaningful experiences for mums and girls – “story over stuff.” Average time spent inside an American Girl store – often a planned outing involving three generations – is over two hours.

Rowland eventually sold the business to Mattel in 1998. The irony of placing her vision in the hands of the company that made Barbie was not lost on her, so she sought reassurances that her brand would maintain its characteristic blend of imagination, history, and values: As Rowland puts it, “chocolate cake with vitamins.”

LUTA: THE FIGHT-WARE BRAND FROM THE FAVELAS

When Luke Dowdney, a British anthropology graduate living in Brazil, took a cab across Rio to meet a girl, he didn’t realise she lived in the heart of the city’s notorious favelas. After getting out of the taxi and turning a corner, he was confronted by a 13-year-old brandishing an M16 rifle.

When Luke Dowdney, a British anthropology graduate living in Brazil, took a cab across Rio to meet a girl, he didn’t realise she lived in the heart of the city’s notorious favelas. After getting out of the taxi and turning a corner, he was confronted by a 13-year-old brandishing an M16 rifle.

His immediate reaction was not one of fear – that came later – but one of sorrow for wasted life. He wondered: ‘What can I do about this?’

As a former British universities’ boxing champion, Dowdney understood the disciplinary power of combat sport. He speaks of it as the “cornerstone” of his youth, giving him focus and a goal to work toward.

Having volunteered in Rio previously, Dowdney was no stranger to seeing kids lose their lives to gang violence. But instead of trying to stop them fighting, he wanted

to get them doing it even more – this time in the ring, rather than on the streets.

In 2000, Dowdney opened a small boxing club called “Luta Pela Paz” (“Fight for Peace”) in a neighborhood where war-grade weaponry was part of the everyday scenery. The idea was for boxing to replicate the macho sense of inclusion that lured so many kids into gang culture, and to be a way of introducing youth work.

By 2011, almost 7,000 youths had gone through an expanded Fight for Peace scheme. Dowdney did not want to rely on pleading for donations; however, he envisaged a new, completely sustainable social model – one where “you ultimately can’t tell if it’s a business or something making a difference to society.” Enter Luta: a new kind of sportswear brand, created by Dowdney with technical help from London art college students and creative input from favela-dwelling kids, an enterprise that ploughs 50 percent of its profits back into Fight for Peace.

Luta – which translates somewhere between “to fight,” “to struggle,” and “to never give up” – was founded on the belief of “real strength.” This belief didn’t come from a team of marketers or a brainstorm meeting. It came from the young people Luke worked with on the “Fight for Peace” program, from watching what they had to endure to get to school or training, or even just to make it through the day.

Luta sportswear is designed for both pro fighters and regular gym-goers keen to “be part of something.” And it seems there’s no shortage of people wanting to tap into the idea of “real strength,” with stockists secured around Europe, and thriving online sales. In 2012, the brand was launched in the United States, where it hopes to continue its success.

THE PASSION BRAND STRATEGIC METHODOLOGY

Objective

The objective is to create a Passion Brand from the basis of an existing brand. What will be set down at the end of the process is a completed Passion Brand strategic codification, but of course, that is more of a beginning than an end, since what really counts is the integrity, commitment, and zeal with which that brief document is translated into action.

And the document will, indeed, be brief – governing the bare headings necessary to capture the essentials of what a Passion Brand is, with belief at the fore. The power of what falls under those headings will reflect the rigor and imagination that the team puts into the process.

Methodology Overview

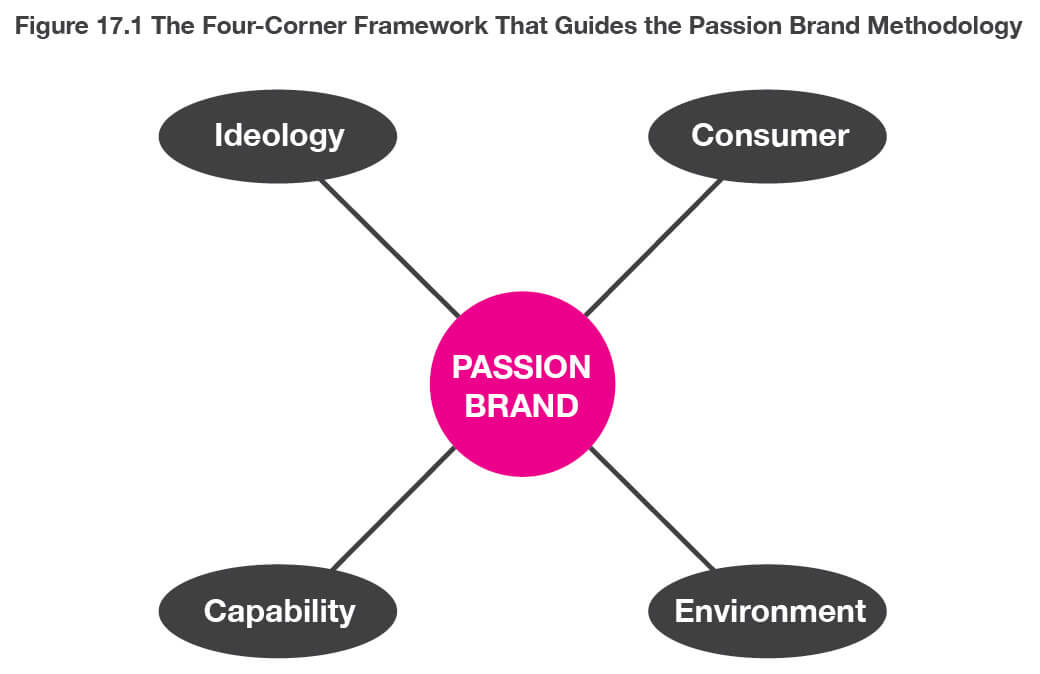

The process splits into two distinct stages, each governed by the framework shown in Figure 17.1. The tasks involved in stage 1 – the more analytical phase – are usually best undertaken by a multidisciplinary team. The tasks in stage 2 – a more dynamic phase in which tough decisions will often need to be made – are usually best handled by a tight, senior team with at least one creative person on board.

Stage 1

The first phase of the process is the rigorous analysis of the subject matter covered by the key words at each of the four corners of the framework. The two corners on the left are internal factors, relating to the brand or company itself. The two corners on the right are external factors, relating to the world beyond the brand. The general aim of stage 1 is to provide the raw materials from which the Passion Brand identity will be forged in stage 2, and to highlight any barriers that might need to be overcome. The more honest, open, and rigorous this analysis, the better the eventual results of stage 2 will be.

Through a process of rigor and imagination the Passion Brand codification emerges at the intersection of the two internal forces (left) and the two external ones (right). Analytical rigor ensures that brand belief is arrived at in full recognition of all the influences and constraints that might impinge upon it; it is never simply something “dreamt up” by a team or individual insulated from reality.

We will now take the four corners in turn, outlining, for each, why the analysis matters, what needs to be captured, and how to go about it, including a few tips and tools to help.

Corner 1: Ideology

Why

The aim is not to crystallize belief – that is for stage 2 – but to throw light on the current and historical ideals, values, and behavioral mores from which an inspiring belief statement might eventually be crafted.

What

An ideological audit of the brand and the organization of which it is a part, governed by three headings:

- Brand history and foundations

- Current stated values and ambitions

- Current day-to-day ideological reality

How

Original Purpose How and why was the brand created? Was it just something opportunistic at the time, or were there deeper roots and reasons? Often it is a case of both, so the subject will repay some exploration. You’re looking for the foundational vision, for the thinking that was big enough to create success out of nothing.

For example, Avon was founded in 1886 by David H. McConnell, a traveling book salesman, after realizing his female customers were far more interested in the free perfume samples he offered than in his books. McConnell also noticed something deeper: that many women were isolated at home while their husbands went off to work. So he purposely recruited female sales representatives from this untapped labor pool, believing they had a natural ability to market to other women. At a time of limited employment options for women, the Avon earnings opportunity was a revolutionary concept.

The ideal of “female empowerment” is still what guides this $10 billion global business today, which styles itself, simply, “The company for women.”

“Living Archives” Talk to people who have been in the company forever – the longest serving employee, people who knew the founders, people who worked at the place or on the brand when it was in its prime. Or talk to industry journalists or venerable commentators with long memories. See what it was that made the brand famous, great, and special in any way.

For example, in 2012, Smith & Nephew, a global healthcare business, was looking to relaunch its longest established and biggest selling wound care brand, Allevyn. Many innovations had been added in to the original, 27-year-old technology, but the team wanted to ensure that the new positioning reflected the truth at the brand’s core. So they traced the sales rep who had sold the first-ever box of Allevyn for his perspective and experience. This, and other similar interviews, strongly influenced the resulting “People First” brand strategy.

Obvious Sources These include statements of values, current mission or vision statements, leadership interviews, annual reports, PR releases, CSR programs, and digital exchanges, anything that might include or hint at an ideological expression of today’s brand.

Behavioral Reality An audit worthy of the name should record practice, not just theory, and often there is considerable variance between the two. Try to get a feel for the behavioral and ethical norms in all markets. You should also probe the extent to which values are respected all the way through the supply chain.

For example, Apple’s stated ideal of “deep collaboration” does not appear to extend to the workforce in some of its Chinese supplier factories, who have had a hard time being heard about “inhuman” working conditions.

Being There It can be revealing – walking the place, taking your meals in the canteen, talking with people who work in the company every day, and getting a feel for the unwritten codes that pervade the organization.

For example, when David Bates took over as the new CEO of Krug, the thing he did for the first three months was nothing. No executive decisions, no reorganizations, no rousing speeches. Instead, as Professor Mark Ritson tells it, he “hung out at the house of Krug, with the ancestors, with the family, at the site of production and he learned about the nature, the style, the ways in which it was done. The guy imbibed the culture the way you’d imbibe the champagne. ”

Corner 2: Capability

Why

The aim is to provide raw material for decisions you will make in stage 2 of the methodology. At that stage you may be looking for ways to improve your end product, or to harmonize capabilities more effectively. Since Passion Brands are about activating belief, since they refuse to become – in Naomi Klein’s memorable phrase – “all strut and no stuff,” you will certainly need to ensure that belief and capability can be aligned.

What

A summary of the capabilities and resources, both tangible and intangible, of the organization behind the brand. These will be broken down into subsections as follows.

- Tangible

- Operational

- Financial

- Assets

- Intangible

- Culture

- Knowledge and relationships

- Reputation

How

Stakeholder Interviews Plan for one-hour interviews with the heads of Operations, Finance, R&D, and HR, plus other specialist leaders according to sector, for example, medical director, in healthcare brands.

Baseline Probing In stage 2 of the methodology it is not uncommon for improvement in capability to become part of the discussion, so you will want to understand what “elasticity” might exist now, or what constraints might need to be overcome, for each of the key capability disciplines.

Open Questions The aim here is twofold: to draw out ideas from leaders of the capability disciplines that no-one might have previously imagined, and to seed the notion that things might need to be done differently down the line, at the end of the process.

- What could we do better?

- If we were creating this business from scratch, in what ways might it (and your function) be different?

- If your budget had to be cut by 50 percent, how would you achieve it? If your budget could be doubled, how would you spend it?

- Looking at your discipline strictly from the customer’s point of view, what is the first thing you would change?

- If this brand didn’t exist, what would people miss? (Potentially a very revealing question, often answered after a long silence.)

Reputation and “Soft Assets” Your audit should seek to honestly appraise the reputation of the brand, and the company behind it, with customers, partners, suppliers, trade commentators, competitors, bank, local community, and, if appropriate, higher levels such as government or civil service.

Social Media Monitoring and Sentiment Analysis A way to assess current reputation among all important audiences. Volume of data is an issue, but there are specialists who can help with sifting and analysis.

Corporate Culture Capability isn’t just about what the organization can do, but what its culture inclines it to do. Is it entrepreneurial? Conservative? Far-sighted? Does it favor self-starters or team players? Does it cherish innovation? Is it “can-do” or “get-permission-first”? Goal or process? Formal or touchy-feely? Understanding these, and other, cultural traits and biases, is another step toward knowing what the brand might be capable of in the future, which developments would be supportable, and which might imply a challenge to cultural norms.

Corner 3: Consumer

Why

A Passion Brand necessarily caries its belief to consumers with exuberance and skill, making it manifest in everything the brand does. This cannot be achieved without a close understanding of the people the brand serves, and the way they live their lives. The aim is illumination, not direction. Relevance is the prize that we seek, which means this consumer understanding must go way beyond the normal category-centric findings of focus groups.

What

The objective is rich description of the people who buy and use the brand, or who might do so in the future. Rich description starts with the basics – who your customers are, and how they relate to the brand – and then progresses to more finely grained detail of behavior, desired self-identity, and the cultural, social, and psychological factors that influence contemporary lives.

How

Research Mix The most important single piece of advice is to use a mix of research methodologies – what academics call triangulation – to identify and corroborate significant underlying themes. Where possible, embrace both qualitative and quantitative techniques. Here are some to consider.

Ethnography This anthropological methodology explores what people are actually doing, as opposed to what they merely report. It typically implies three to six weeks of observation, in the appropriate real-life context, with video running much of the time. What it produces are rich, actionable discoveries that might not have been uncovered by standard techniques alone.

Ethnography Lite This is to be considered when time, cost, or practicality rule out a full ethnographic study. Audio diaries, video diaries, and accompanied shopping trips all make use of established ethnographic concepts, and capture the sights, sounds, and spontaneous feelings of people in real-time, real-life contexts.

Cooperative Inquiry This is an interesting technique from the social sciences, only recently pioneered for commercial use. The idea is to erase the line between researcher and respondent, observer and observed; instead the technique produces “active subjects,” fully aware of the research objectives, and fully participating in the generation of findings.

Employee Insights on Customers Potentially illuminating, especially in service industries, a favorite technique of Apple and Emirates.

Social Listening Get a feel for the prevailing themes in your customers’ lives through the analysis of relevant conversations and content in social media: blogs, social networks, and forums.

Conjoint Analysis This quant methodology is still the most useful tool for determining the relative importance people put on product or category features, including price. By forcing respondents to repeatedly trade off pairs of values, and assigning weightings to each as it goes along, it can capture the optimum combination with a high degree of confidence.

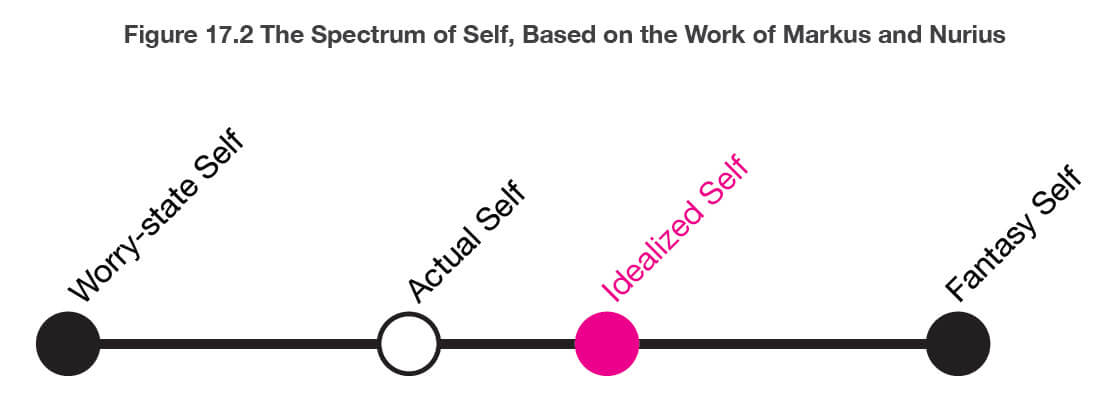

Idealized-Self Mapping The Idealized Self is the most interesting thing you can know about your customers. It is part of the Theory of Possible Selves from the seminal 1986 paper by the U.S. psychologists Markus and Nurius.

Figure 17.2 gives you a simple way to imagine it, a bit like a metro map. The Actual Self is everyday reality. Nobody wants to make the journey backward, toward Worry-state Self; everyone makes the mental journey across to Fantasy Self, but in only daydreams, not in reality. The journey that people are powerfully motivated to make is the short one from Actual Self to Idealized Self: the person they are at their best.

People Are Powerfully Cognitively Motivated to Make the Journey from Actual to Idealized Self.

Corner 4: Environment

Why

Brand ambitions can be helped or held in check by factors in the wider competitive environment, so here we look at everything from competitor activity to upcoming legislation. Since the competitive environment is in constant flux, and since you will need to project forward in the second phase of the methodology, some sense of prevailing trends, as well the documentation of current facts, is required.

What

A summary or presentation governed by the following headings:

- Micro

- The category and its assumptions

- b. The immediate competitive set

- Category hotspots and warning signs

- Macro

- The Big Five factors

- Macro hot-spots and warning signs

How

Category Basics How do you define the category in which your brand operates? What are the main strategic divisions within it?

Category Assumptions Note all the generally accepted success factors without which it is tacitly agreed that no brand in the category can prosper. Then – much harder, but tremendously useful for the second stage of the methodology – probe which of these might be open to question, or challenged by a brand determined to gain leadership by doing things differently. (The Value Curve, from Insead’s Kim and Mauborgne, is a useful tool here.)

Who–What–How Analysis This deceptively simple format is often the most revealing way to assess competitive strength and direction of travel. Simply capture, for each relevant competitor, who they are targeting, with what products or services, and how they deliver their offer to customers.

The Big Five factors The five macro factors are demographics, economics, socio-politics, legislation, and technology. Anyone who’s done a PEST analysis (Politics, Economics, Social, Technology) will have confronted something similar, but while that stalwart of MBA programs is designed for overall corporate strategic planning, our five factors would be captured as they relate specifically to the brand and its future.

Talk to Trade Gurus, Journos, and Bloggers Sometimes business teams can be so caught up in their own brand world that they fail to perceive important category hot spots and warning signs. Often trade gurus, journalists, and bloggers, with their finely spun networks and frequent contacts, can be the most informed and up-to-the-minute sources of valuable information: what is coming round the corner and why, which initiatives are making an impression and which are drawing flak. Court them; they love to share.

Stage 2

Stage 2 opens with a debrief and discussion of the four corners of analysis. It will close with the team capturing the essentials of their Passion Brand strategic codification – belief, role, forever values, idealized self, and connecting idea.

Between those two points is a structured process created deliberately to tease out from the four-corner debrief not just themes, but also, and much more importantly, tensions. And there will be tensions – most typically between what the brand espouses in its current values set and what it actually has to do to make money. It is the heat generated by tensions, and the creativity and soul-searching needed to resolve them, that propels the team to decide what really matters, what sacrifices might need to be made, and what must be done differently in the future.

Example: A global brand audit for the NGO Fairtrade, which lobbies for a better deal for developing-world farmers, showed “youth” to be a common theme. Every market reported that the brand needed to do more to be relevant to a new generation. The tension was clear, though: older consumers accounted for over 80 percent of all Fairtrade purchasing, so alienating them would be a serious financial issue. This tension helped the team focus on a positioning concept centered on personal empowerment – The Power of You – that could unite and inspire both audiences.

The Passion Questions

This is the process by which tensions are thrown into sharp relief, and rounded on by the team. Each passion question is designed to pit two different corners of the analysis against each other, to probe for incompatibilities or contradictions between them. Since the permutations of two from four is six, that is the number of passion questions to resolve.

Question 1: What Are We Good at That Is Good for People?

This question is designed to push the team deep into the “capability” and “consumer” corners. Probe your capability hard and describe with guts and flair the real significance it assumes in people’s lives. What is your company’s deep purpose? How does your brand improve lives? Why does it have a right to exist? You are taking the first tentative steps toward revealing your brand belief.

Example: Johnson & Johnson’s personal lubricant product, KY, had always been sold as a “problem-solution” functional aid. In 2003, the team explored the deeper emotional significance that the brand fostered, the enhancement of “healthy intimacy,” and all the human benefits that ensue from that. The brand was successfully relaunched based on a belief that centered on the importance of passionate intimacy in people’s lives.

Question 2: Which Values Will We Still Hold When the World Moves on?

This question connects the “ideology” and “environment” corners. It is quite normal for the ideological audit to have thrown up a fairly long list of values at the levels of both the brand and the organization behind it. By projecting forward, and imagining how the future competitive environment might look, in perhaps five or ten years time, it forces the team to consider which values are for all time, and which are merely serving a convenient purpose for now.

Example: See the panel on Camper. Note how the shoe brand’s values are bound up within a deeper concept – respect for the peasant way of life – and how this links seamlessly with the brand’s overall belief. These are “forever values,” from which the brand will not shift no matter how fast and crazy our world becomes. They are grounding, in every sense.

Question 3: What Should We Stop Doing Now in Order to Stay True to Our Values?

This question links “ideology” and “capability.” It forces the team to examine its most cherished values in the light of commercial reality – all the things the company does to survive, thrive, and meet those shareholder demands. Principles-versus-profit is therefore one inevitable turn for the debate to take. Values integrity is the outcome that must be sought.

Example: Starbucks has always been proud to display its tenets of good global citizenship in its stores. Yet it came under fire from activists for alleged exploitation of third-world farmers. Starbucks responded by completely reviewing its supply chain, clarifying the environmental and social criteria it would now demand, and dropping suppliers who wouldn’t meet them or demand them in turn of those further back in the chain. In so doing, it improved its values integrity.

Question 4: How Is Our Industry Currently Letting People Down?

This question links “consumer” and “environment” and is by no means as simple as it might seem. It is not confined to inquiring what consumer “unmet needs” might be. The question has a deeper purpose: to look at how your industry quietly, unthinkingly, perhaps even cynically, mis-serves people in ways of which they are not yet aware.

Example: For 20 years, Staples was the leading office supplies retailer in the United States. When growth slowed in the late 1990s, it did a simple thing: just followed shoppers round the store and observed. The team was struck by how an industry norm made things harder for customers: the things they bought most regularly – printer ink and paper – were placed at the back of the store, to entice impulse purchases. Staples decided to break that norm, moving the items to the front of the store, as part of a whole range of initiatives to make things easier for customers. “Easy” became the brand’s one-word customer promise; renewed brand leadership was the reward.

Question 5: How Might Our Historical Ethos Be Reinterpreted for People Today?

This question links “ideology” and “consumer.” It looks your brand’s values, roots, and ethos, and plots them against today’s life, as lived by today’s consumers. The aim isn’t to allow consumers to dictate what your ethos and values should be, but to ensure that their expression – in everything the brand does – is framed with relevance for modern life.

Example: See the panel on Ford.

Question 6: What Is Our Future Credible Capability?

This question actually links all four of the corners of analysis. “Capability” is obviously involved, since the aim is to imagine how the organization might be able to develop its capability in the coming years. The word “credible” hints at the wider task: to explore future capability in light of imagined future consumer needs, the projected future shape of the market, and deeply held organizational values. All four corners are therefore necessarily involved.

FORD: REINTERPRETING FOUNDATIONAL BELIEF

In 1903, Henry Ford founded his eponymous brand with an uncompromising vision: “To open up the highways for all mankind.” It was always a democratizing mantra: a belief that the ordinary man had a right to extend his horizons – physically, and therefore commercially – and achieve more from life.

Ford grew to become the world’s No. 2 automaker, close on the heels of GM. There were troughs, though, too – often felt by insiders to be those times when the brand “moved away from its true self.”

The financial crisis brought an all-time low, with the business teetering on bankruptcy. Alongside the macro problems were some that had been self-imposed: a loss of focus through the acquisitions of Volvo, Jaguar, Land Rover, and Aston Martin, and intercine rivalry between Ford divisions and geographical units.

In 2008, the new CEO Alan Mulally instigated a strategy of simplification under the banner “One Ford.” He divested the brand of its acquired marques, and challenged his team to reframe Ford’s statement of “deep purpose.” Headed by Executive Vice President, Global Marketing, Sales and Service, Jim Farley, a small team of leaders from global markets, along with communications agency Team Detroit, began to probe for the “soul of the organization.”

The team kept returning to Henry Ford’s original vision. Though its literal meaning was outdated for modern life, they noted a deeper meaning that lay in those original words. For ordinary people, Ford had also opened up “new highways of possibility.” That deeper meaning still held. The brand’s natural blue-collar franchise – people looking to the future and striving to move forward – was well served by Ford’s range of modestly priced vehicles, including workhorse trucks and vans, as well as cars.

The ensuing brand belief focused on the significance of “helping people go further in their lives.” It was captured pithily with a two-word connecting idea: “Go further.” Significantly, the business capitalized on this as an internal mantra, too, galvanizing its own people to go further in their quest to serve customers better.

CRYSTALLIZING THE PASSION BRAND STRATEGIC CODIFICATION

The passion questions should have helped you close the gap between analysis and its ultimate distillation. They should have helped you glimpse your brand belief, reduce and refine your values, sharpen your view on the market, and reveal what is special about your core.

Now is the time to allow imagination and courage to come to the fore and to set down, as crisply and memorably as possible, the codification by which the brand is prepared to live and develop long into the future.

There are five headings that will capture that future brand.

Belief

This is the brand’s take on the world, a view on what would make the world a little better. Aim to inspire: a statement of belief should be at once connected to, and yet bigger than, the category in which the brand exists.

Role

This is a statement of what the brand actually does to bring about the furtherance of its belief. These first two statements taken together amount to the brand’s deep purpose in the world.

Forever Values

The list should be potent yet spare: three or four values, simply stated, strongly felt; values that will be held even when the world moves on. Do not be afraid to use words outside the accepted business lexicon.

Idealized Self

This is about your customers. It is a brief description not of who they are, but of who they want to be: the self they imagine and aspire to in moments of reflection, the better version of themselves that transcends day-to-day reality. Both practically and symbolically, your brand should help them on their journey from actual to idealized self.

Connecting Idea

The simple phrase that connects your brand belief with consumers. Pithy, motivating, and brief, and therefore a natural contender for a slogan, it should unite all aspects of the brand’s outward expression, from behavior to communications.

Lorenzo Fluxá

Camper was founded in 1985 by the fourth-generation shoemaker Lorenzo Fluxá in his native Majorca. It is now a global brand, with a dedicated following, trading from over 100 of its own stores, with sales of $300 million. Fluxá has always promulgated a belief in slowness: He feels we are all too obsessed with speed in our modern lives, and counsels us to slow down and take in the beautiful world around us. The brand’s iconography is deliberately earthy – the word “camper” means “peasant” in Catalan, and the brand’s stated values are those of the peasant way of life. The full strategic codification below was extrapolated from an interview with Lorenzo Fluxá conducted by Dr Helen Edwards in 2004.

Belief

On life’s journey, slow is more rewarding than fast

Role

To provide the safest and cheapest vehicles possible – comfortable shoes

Forever Values

Austerity, simplicity, discretion

Idealized Self

Creative but grounded

Connecting Idea

The Walking Society

A New Brand Future

The crystallization of a Passion Brand identity is the end of a process but the beginning of a new future for the brand. It is one that will demand total integrity – such that everyone in the organization intuitively “feels” the brand – and the kind of imagination that can keep the belief relevant in an ever-changing world. The reward for this endeavor is the renewed enthusiasm of employees, suppliers, and partners, and deeper emotional engagement with consumers, as they welcome this belief-led entity inside their membrane of self. The feelings are not so bad for leadership, either – to be part of a brand that counts for something in the world, socially as well as commercially, in that forest of tall trees, standing taller for all the right reasons.