The Moral Minority

Passing fad or 21st century route to market dominance?

Helen Edwards & Derek Day look at the methods and the motivations of a new breed of ethical marketers

In Sam Roddick’s Covent Garden ‘erotic emporium’, Coco de Mer, you can buy a Fair Trade spanking paddle. Like everything else in the shop, it is ethically sourced, reflecting the brand’s commitment to sustainable production and support for local economies. “I do believe in capitalism and pleasure”, says Roddick, “but no one should have to suffer because of it.” Not unless they want to, of course.

Coco de Mer, with its dildos made from naturally felled wood, and non-toxic sex toys endorsed by the World Wildlife Fund, is an indication of how far the concept of moral marketing has travelled since Roddick’s parents founded the Body Shop 30 years ago. Today, brands built on strong ethical and environmental principles are blazing a trail in sectors as diverse as chocolate and banking. Innocent, Green & Black’s, Banyan Tree and The Co-operative Bank are all examples of brands that successfully combine a strong product offer with an appeal to the consumer’s increasingly sensitised conscience.

Is this a passing fad, or is it evidence of a seismic shift in the way brands engage with the world? Mike Gidney, Director of Policy at Traidcraft, a fairtrade organisation, is in no doubt that the fundamentals have changed. “The old model – that business is business, making its contribution through tax and employment – isn’t enough anymore,” he claims, citing Nestle as the classic example of the outmoded approach. Innocent’s Richard Reed, describing himself as “part hippy, part capitalist”, believes that “the current capitalist system isn’t going anywhere”. He says he aims to “embarrass the big food companies by taking market share. Consumers want something that’s produced in a responsible manner and I want to show that there’s cash in it.”

It would seem that there is. Innocent has grown from scratch in 1999 to £35 million today, with 50% of the UK smoothies market. The company, which was founded by three friends ‘intent on doing a bit of good’, backs its quirkily-expressed, eco-humanist values with an annual donation of 10% of profit to re-forestation projects in the fruit growing regions of the world. A similar concern for indigenous cultivation has been a factor in Green & Black’s spectacular marketing progress. “There is no doubt that our ethical attributes helped us get distribution in the big chains,” says Mark Palmer, recently voted Marketer of the Year. The brand achieved 70% growth in 2004, compared with just 2% for the chocolate category as a whole. Meanwhile, The Co-operative Bank, which summarises its approach as ‘profit with principles’, saw retail customer deposits soar from £1 billion to £6 billion in the decade following its relaunch as an ethical bank.

Mainstream or niche?

But while all of these brands are outstripping the growth of their sectors, none of them is huge in absolute terms. This sparks the question of whether moral marketing is still really a niche ploy. Estimates of the current size of the ethical market vary widely, partly as a consequence of the difficulty of defining terms. The Co-operative Bank’s latest Ethical Consumerism Report puts it at £25 billion, but that includes boycotts and £9 billion of indirect investment business. Direct spending by consumers on ethical products and services, at £8.75 billion, amounts to some 4% of the total consumer pot. But Simon Williams, Director of Corporate Affairs at The Co-operative Bank, is dismissive of the niche argument. “Four in ten eggs bought in the UK are now free-range, despite the higher price”, he says. “That is not a niche.”

Perhaps the simplicity of that choice – free-range or not – is part of the reason for that mass market success. The difficulty comes with the multi-choice questions facing consumers as they negotiate the hypermarket aisles. Is this a Fair Trade product? Have any animals been harmed in its production? Is it organic? Is the packaging carbon-neutral? Does the company that makes it use green energy? What about the companies that supply to them? “It is confusing for customers”, admits Mike Gidney. “You need a degree in social science to go shopping.”

But Michael Willmott, Co-founder and Director of the Future Foundation, believes it doesn’t work like that. He sees ethical image as more of a snap-decision tiebreaker between increasingly similar offers. “We’re working on some theory that as choice expands consumers can’t take it in and they act more intuitively around fundamentals – are these good guys?”

Multinational options

The need to be seen on the side of good is increasingly exercising minds at the big multinationals, alarmed at the sudden intrusion on share by specialist ethical brands. From a practical point of view they are faced with two strategic choices: buy the halo, or earn it. Neither is an easy fix.

The first route has seen the acquisition of Ben and Jerry’s by Unilever, Green and Black’s by Cadbury and 30% of Prêt a Manger by McDonald’s. But in each case the larger company has been at pains to underline the stand-alone status of its newly acquired brand. There is no evidence that the main brands have enjoyed any extra respect for their own ethical credentials as a result of the acquisition, although Mark Palmer believes it can have a positive, ‘feel-good’ effect internally.

The second approach – earning the ‘good guy’ tag through better practice – can imply an overhaul of company policy so broad-ranging as to make shareholders shudder. Consumers might rely on shallow hunches in their judgement of good and bad, but their antennae are finely tuned for humbug, and they are aided in their choices by pressure groups and bloggers intent on exposing any deviation between what a company says and how it actually behaves. Moral marketing can never amount to just a tacked-on CSR programme; the brand must be seen to do good in its day job, with its ethical principles holding throughout the organisation. At The Co-operative Bank, for example, ethical considerations affect even the choice of toilet paper in the staff washrooms – and it is the staff themselves that do the choosing, based on their own investigations into the eco-credentials of the available options.

The larger the company and the more established its ways, the harder it is to get right. As Mark Palmer observes, “It’s much easier for companies like Green & Black’s, and Innocent to take this holistic approach because it’s never been an on-cost; it’s always been a part of their way of doing business.”

A challenge to that view comes from an unexpected quarter. “Shareholders are important”, says David Hudson, Communication and Corporate Affairs Director at Nestle, “but we work to a triple bottom line where we have to deliver on social, environmental and economic dimensions. Increasingly our ethical standards will become more apparent at a brand, rather than just corporate, level.”

Adrian Hosford, Director of CSR at BT, points out that shareholder return is not always at odds with environmental good. “We now have 25% of our people working from home”, he says, “saving the business £400 million last year. But that also reduces travel and the energy costs that go with it, as well as giving people a better quality of life.” He goes on to observe that it isn’t just customers that care about ethics: “One third of our graduate applicants cite BT’s achievements in sustainable development as a reason for their interest in the company.”

The future

But however hard big business works on its ethical reputation, the reality is that the smaller moral marketers can make things tough by continually moving the game on. Richard Reed wants Innocent to become the first ‘fmsg’ brand – where the ‘s’ stands for sustainable. “At the moment, 25% of our packaging is recycled; I want to be a 100% recycled business. I want our business system to have either a zero or positive environmental impact. Big companies can also do this, but it doesn’t work well for quarterly shareholder reporting.”

Eventually, Mark Palmer sees a kind of two-tier moral market evolving. “Ethical trading will be a requisite”, he says, “but there will be some blurring and confusion. In 10 years there will be the super-ethical niche brands – and bigger brands that carry that spirit into the mainstream.”

However it pans out it is clear that, from eggs to dildos, morality has finally become sexy.

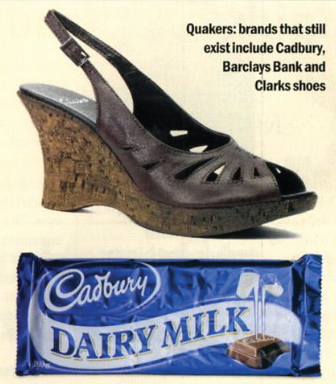

The Quakers – the original moral marketers

Ethical marketing is not the 21st century phenomenon it first appears. Its antecedents reach back at least two centuries to the unique commercial morality of the Quakers, the essence of which was that business prosperity was both achieved and justified by being good at something that is good for people. In an era when it was common for retailers to add water to butter, and chalk to flour, as well as to cheat at scales, the resolute honesty of the Quakers attracted a large and loyal following. Some of the brands they founded still prosper today, including Cadbury, Clark’s Shoes, Price Waterhouse, Barclay’s and Lloyds (but not the once-famous brand of oats, which was a phoney).

The acquisition of Green & Black’s by Cadbury Schweppes is therefore apt, and Mark Palmer confirms that Cadbury’s Quaker heritage was a factor in the deal. “We were looking for a good fit. The ethical roots of Cadbury’s business are strong. We needed investment and during a three-year getting-to-know period, Cadbury’s were respectful of what had been achieved.”

Innocent

Founded: 1999.

Moral stance: Combines a belief in product purity with eco-humanist values. Resolutely refuses to use concentrates and accepts less margin as a consequence. Supports reforestation projects and NGOs in the poorer fruit-growing regions of the world. Does it all with characteristic lightness of touch.

Moral stance: Combines a belief in product purity with eco-humanist values. Resolutely refuses to use concentrates and accepts less margin as a consequence. Supports reforestation projects and NGOs in the poorer fruit-growing regions of the world. Does it all with characteristic lightness of touch.

Commercial performance: Built from scratch into a £35 million brand in six years. Now brand leader in the UK smoothies market with 50% share. Grew 110% in 2004.

Next big challenge: To make the transition from the £70 million UK smoothies market to the £11 billion UK soft drinks market.

The Co-operative Bank

Founded: 1872 (relaunched as the ethical bank in 1992)

Moral stance: Will not invest “its customers’ money” in areas it deems unethical. These include tobacco, the fur trade, industries that exploit animals, companies that pollute and countries with oppressive regimes. Vigorous champion for the ethical business movement and publishes Ethical Consumerism Report annually.

Moral stance: Will not invest “its customers’ money” in areas it deems unethical. These include tobacco, the fur trade, industries that exploit animals, companies that pollute and countries with oppressive regimes. Vigorous champion for the ethical business movement and publishes Ethical Consumerism Report annually.

Commercial performance: Retail customer deposits grew from £1 billion to £6 billion in the decade following its relaunch as an ethical bank.

Next big challenge: The burning question has long been why Co-op food stores couldn’t emulate the bank’s success through mainstream ethical marketing. But ethics can’t compensate for a poor product – and Co-op stores have long trailed the leaders in the basics.

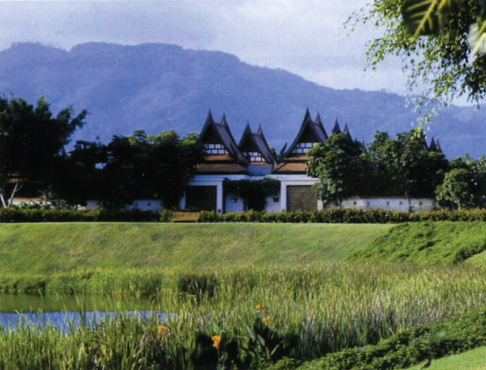

Banyan Tree Hotels & Resorts

Founded: Launched first resort in Phuket, 1994.

Moral stance: Champions eco-tourism. Values ecology and beauty of natural environment and strives for social and economic progress in less developed areas. Transformed abandoned tin mine into Phuket resort. Built Vabbinfaru resort, Maldives, using small boats to transport materials to avoid harming coral reef.

Moral stance: Champions eco-tourism. Values ecology and beauty of natural environment and strives for social and economic progress in less developed areas. Transformed abandoned tin mine into Phuket resort. Built Vabbinfaru resort, Maldives, using small boats to transport materials to avoid harming coral reef.

Commercial performance: Grown from one resort to 16 in 11 years, with 46 spas and 49 retail galleries in 19 countries worldwide.

Next big challenge: Launching Banyan Tree Ringha, China, in 2006.

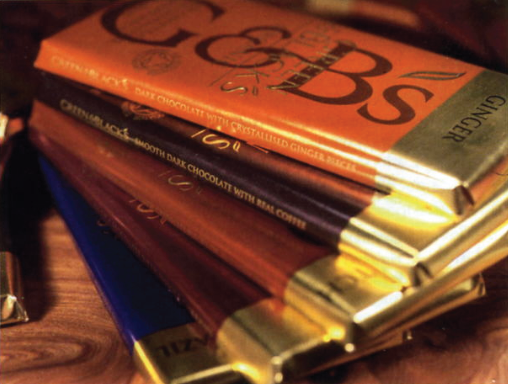

Green & Black’s

Founded: 1991.

Moral stance: Maya Gold chocolate was first ever Fairtrade product to be sold in Britain. Pays farmers premium and additional Fairtrade price, while long-term contracts allows them to improve quality of life. Variety of trees within cocoa farms increases biodiversity and fights diseases. Doesn’t spray cocoa with pesticides so farmers avoid related health problems.

Moral stance: Maya Gold chocolate was first ever Fairtrade product to be sold in Britain. Pays farmers premium and additional Fairtrade price, while long-term contracts allows them to improve quality of life. Variety of trees within cocoa farms increases biodiversity and fights diseases. Doesn’t spray cocoa with pesticides so farmers avoid related health problems.

Commercial performance: UK’s fastest growing confectionary brand. Grew 67% in 2003, and 70% in 2004. Now has 5.1% of UK market for block chocolate. Latest sales: £22.4m. Acquired by Cadbury Schweppes in £20 million deal, May 2005.

Next big challenge: To perform on an international stage as a part of Cadbury’s.